A Challenge, Answered

Paul DePace ’68, M.B.A. ’75, was in his junior year at URI when a car accident cost him the use of his legs. He’s gone on to be an athlete, a coach, and an international activist for sports for people with disabilities—while shaping a 40-year career at the University of Rhode Island.

By Pippa Jack

It’s 1957, and Paul DePace wears a tie every day to George West Junior High in Providence’s Mount Pleasant neighborhood. Ties are not required, which may be part of why he takes a bit of ribbing from his classmates. But his parents’ clothing store is nearby and his father wears a tie every day, so the kid with track ambitions runs across the street from his parents’ home and directly into school every morning, usually a little late, necktie flying.

It’s 1965, and DePace has joined Chi Phi, the fraternity that used to sit on Upper College Road. “I was learning a lot of things,” he says, “just not in class.” The price of that education: the letter the Dean of Students writes to his parents putting him on social probation.

It’s 1966, and DePace is taking a year out of college, searching for focus.

It’s early 1967, and DePace comes to for a brief moment, lying alone on the side of a snowy road in Narragansett. Then there’s the feeling of warm oil on his forehead, and he opens his eyes to find himself on a hospital bed, a priest bending over him to administer last rites. “I’m not going anywhere,” DePace tells him, “and I don’t use oil on my hair.”

The next time he opens his eyes, his parents are there, and so are the doctors.

It was a mere 18 months later when DePace graduated, triumphantly, from URI, an achievement he sums up as having gone “from the Dean of Student’s disciplinary list to the Dean’s list.” The phrase, with typical humor, vastly undersells the determination that carried him through a brief summer of rehab, his parents and friends rallying around, never allowing himself to wallow; and the renewed vigor he brought to his course work when he returned to finish his last year as a commuter. He went on to score an engineering position at Raytheon right out of college. His career took him next to Electric Boat, then, with his M.B.A. and professional engineer’s license under his belt, to a job at his alma mater, where he started as director of URI’s physical plant. In the 40-odd years since, he’s overseen about a billion dollars’ worth of construction and renovation, adding a million and a half square feet to the University’s footprint, all of it wheelchair-accessible—even before the ADA came into law in 1990. There aren’t many buildings on campus that DePace, now director of capital projects, hasn’t touched. During the Blizzard of ’78, while his staff plowed and worked at getting the University’s power restored, he slept on the floor of his office for four nights. He was around for the creation of the old Visitors Center, which is now being replaced by the Welcome Center, “which is how I know I’ve worked here a really long time, to be demolishing something I built.”

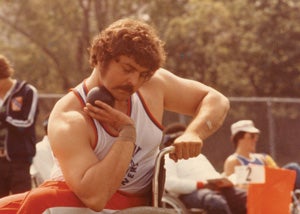

But his engineering career is just one facet of DePace’s life. Back in the summer of 1968, just a few days after graduation, he impulsively drove up to the Crotched Mountain Rehab Center in New Hampshire, where he sat, alone, on the sidelines at his first wheelchair sports meet. It was a friendly, if unsophisticated, event, and the next year, he was back. He competed in pretty much any sport he thought he had a chance at: discus, javelin and shot put (in the absence of other ways to secure his wheelchair when he threw, a large friend had to anchor it from below). Long-buried track-and-field ambitions joyfully resurfaced. In 1971, he went further, forming a wheelchair basketball team; soon he added powerlifting, a sport that took him to international competition before shoulder injuries sidelined him in the 1990s. Competing or not, sports for people with disabilities had “gotten into my blood, and there was no cure.” So he started coaching, as well as taking on local activist and administrative roles.

He was operating in a context of sweeping historical change. After World War II, the combination of improved transportation and the advent of penicillin meant that instead of perishing on the battlefield, injured soldiers came home, still young and active. At Stoke Mandeville Hospital in Aylesbury, England, in the late 1940s, sports for people with disabilities was born. Over the following decades, both in the U.K. and the U.S., a quiet but profound social revolution ensued. The first Paralympic Games were held in Rome in 1960. Advances were slow; it was 1976 when the first Winter Paralympic Games took place in Sweden.

More victories have followed, and DePace has been at the frontlines. The first time he went to see the Summer Paralympics was Toronto in 1976. The Olympics that year took place in Montreal, but the Paralympians weren’t considered part of the Olympic fold, and had to raise all the money they needed to compete. But aspiring Paralympic athletes kept showing up, and so did DePace. His mother once told him “never to join an organization I couldn’t become president of,” and it’s advice he internalized, leading successively larger organizations as they lobbied for access, for changes in law, for parity in support. He was a founding member and president of People Actively Reaching Independence (PARI), formerly Paraplegia Association of Rhode Island, and president of International Wheelchair and Amputee Sports Federation (IWAS) for 16 years. By Atlanta (’96), he was a member of the Paralympic Games Organizing Board. At the 2000 games in Sydney, the U.S. Olympic Committee took over responsibility for the 500-or-so American athletes and coaches that compete each year in the Paralympics.

DePace has traveled the world and earned all sorts of accolades. He carried the torch in Salt Lake City and Athens, served as Chef De Mission for the Barcelona ’92 games, was inducted into the Wheelchair Sports Hall of Fame in Las Vegas, and most recently, in late 2017, was named to the Paralympic Order for outstanding service to the Paralympic cause at a ceremony in Abu Dhabi. Along the way, he has logged some 700,000 frequent flier miles, and seen “all the wonders of the ancient world—the Great Wall of China, the Pyramids, the Acropolis—and a lot of hotel conference rooms.” And then there are all the stories, like the time he was assigned a security detail in Athens that included a driver, a squad car with two more cops, and a motorcycle tail. When it became clear DePace wasn’t a target for the terrorist threats flying around in 2004, the five spent their time enjoying fabulous meals at the officers’ family homes.

It’s all been richer, more jet-setting, more significant, than that geeky, chronically late middle schooler in Mount Pleasant could ever have dreamt. He’s winding down the travel now, and was happy to step down to the president emeritus position on the IWAS Board. But looking back, there isn’t a thing he would change—not even that January night when his car spun out and hit a stone wall. “It opened up a whole new opportunity for experiences I wouldn’t have had otherwise,” he reflects. “I wouldn’t have met the love of my life, I wouldn’t have had lasting relationships with people all over the world. It was get focused or be lost. I think it was a surprise to everyone when I decided to get focused.”•

Home

Home Browse

Browse Close

Close Events

Events Maps

Maps Email

Email Brightspace

Brightspace eCampus

eCampus