5-Minute Expert: The Fight to Distribute a Lifesaving Drug

By Elizabeth Rau

naloxone

noun | nal·ox·one | /na-läk-sn/ A synthetic potent antagonist of narcotic drugs

Sales of prescription opioid painkillers have climbed 400 percent in the last 15 years in the U.S., while overdose deaths from opioids and heroin have gone up 200 percent. What’s going on in the bodies of people involved in this national tragedy? A deadly overdose slows breathing. Its signs: respiratory distress, clammy skin, blue lips.

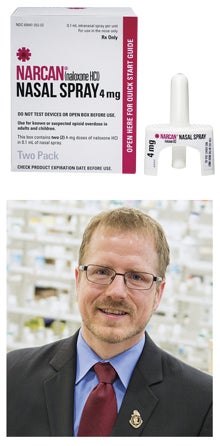

Naloxone, approved by the Food and Drug Administration in the early 1970s and administered through a needle or as a nasal spray, works by displacing the opiate from its receptors in the brain. It reverses the effects of the drug in a few minutes—people wake up and breathe again. It costs about $100 per kit, which is covered, at least in Rhode Island, by public and private health insurance.

When fentanyl-laced heroin and opioid pain relievers like Oxycontin and Vicodin started killing tens of thousands of Americans, police departments began outfitting their officers with the lifesaving medication, often known as Narcan. Now URI pharmacy professor Jeffrey Bratberg wants to go a step further, and his idea is gaining traction across the nation: Distribute naloxone from pharmacies to users—and their friends and families.

“Pharmacies are ideal locations for caregivers to ask for help for their loved ones,’’ he says.

An infectious disease specialist with a focus on public health, Bratberg researched the role of pharmacists in bioterrorism and natural disaster responses for years, assisting with the state’s H1N1 swine flu epidemic and aiding victims of Hurricane Katrina. Then he learned that Rhode Island had one of the highest rates of fatal overdoses in the country: In the last five years alone, the number of overdose deaths in the state has grown by 73 percent, to 243 deaths in 2014.

Bratberg teamed up with his colleagues and doctors to develop a program that allows anyone to obtain naloxone from a participating pharmacist. The Walgreens pharmacy chain was the first to join, then CVS and Rite Aid. Bratberg also enlisted Tara Thomas, Pharm.D. ’13, who created an online training course on overdose signs and recommended addiction treatment centers.

“Pharmacists play an essential role in medication safety for all patients getting opioids,’’ says Bratberg, who is working with researchers at Boston Medical Center on a $1.3 million federal grant to create best practices for naloxone distribution by pharmacists. “Make no mistake about it: Pharmacists are at the forefront of the nation’s opioid epidemic.’’

Skeptics say people will use naloxone as an excuse to continue their drug use without fear of an overdose. Bratberg’s response: “It’s not a moral failing to be a chronic drug user. It’s a disease. Do we lock up people with diabetes because they ate too much sugar? No. As a society we have a moral obligation to treat people with chronic diseases.’’

One day, naloxone may be offered over-the-counter, much like a cold pill. Australia sells it that way, and Canada is expected to follow this summer. •

Home

Home Browse

Browse Close

Close Events

Events Maps

Maps Email

Email Brightspace

Brightspace eCampus

eCampus