Conservation Specialist

The recession has made it difficult for college graduates to land jobs in their specialties, but one recent URI alum has not only found his dream job—he found it in a tropical paradise.

Ben Vinhateiro graduated in December 2008 with a B.S. in Environmental Science and Management from the Department of Natural Resources Science (NRS) in the College of the Environment and Life Sciences. En route to his degree, he had the unique distinction of conducting his own project at URI’s Peckham Farm where he demonstrated how small farms can reduce polluted runoff from paddocks.

It’s unusual for an undergrad to run his own project, noted Professor Arthur Gold, Vinhateiro’s NRS mentor, but Ben did it and received quite a bit of publicity about his project at the time.

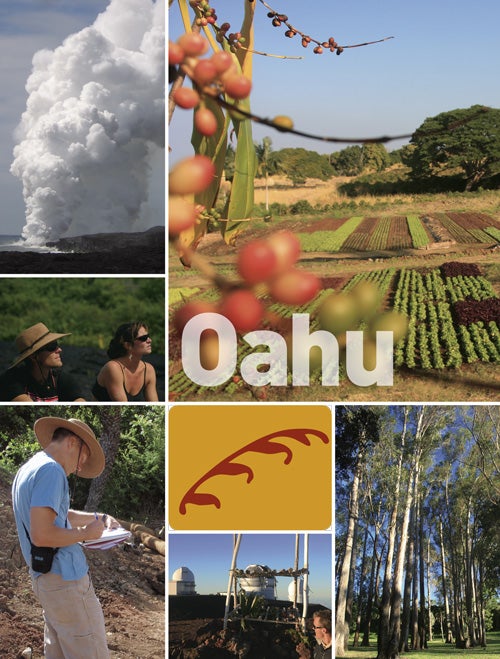

It turns out that experience—plus a great deal of accidental good fortune—helped Vinhateiro land a job as a conservation specialist for the entire island of Oahu. He started the job in June 2009 and has already fallen in love with the climate, the people, the terrain and his duties as one of only two paid conservation specialists on an island that is roughly half the size of Rhode Island.

Vinhateiro is paid via a two-year grant from the U.S. Department of Health because his job has mainly to do with water quality and quantity for a host of users, from developers to farmers. Using standards established by the Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS), he assists landowners with managing their water resources so that they have plenty when Mother Nature is stingy and can conserve when Mother Nature is too generous—as can happen on a tropical island.

“I hope to stay here a long time,” Vinhateiro said by phone in a recent interview, noting that funding for the position is traditionally renewed every two years.

How he ended up in Hawaii so far from his native South Kingstown involved a bit of serendipity. After graduation Vinhateiro booked passage on a research cruise through URI’s Graduate School of Oceanography. “It was a cool opportunity,” he said, “a free ride from Costa Rica to Hawaii.” En route he started checking job opportunities, and an ad for a conservation specialist on Oahu “just popped up.”

In May 2009 the Oahu authorities offered him the job: “My URI degree and my past experience helped me get the job,” he said. In particular, the project he ran at Peckham Farm turned out to be “my bread and butter project; that sort of water management is just what I’m doing now.”

There are myriad water quality issues on the island. Mountain ridges help create unusual weather patterns with the east side of the island getting more rain. At times there can be too much rain, and so there are erosion issues. In addition, farmers want to store water for the times when the rain does not fall. Mulches and water containment structures, both artificial and natural, can be employed to help recharge the aquifer.

Vinhateiro works for three conservation districts that cover the island. Like conservation districts in Rhode Island, each district has an all-volunteer board.

While there are occasions where he works with NRCS, which can offer partial grants to farmers, the bulk of his work is providing advice and information for landowners who wish to remain independent of government funding and either do the work themselves or contract it out.

“There are many ways the conservation district can help,” he says, adding that usually he approaches each project by looking at it from all angles including air, water, soil, plants, and animals. “We also have to consider the human component as well—such as what kind of labor is involved and cost factors.”

Vinhateiro and his wife, Karuna, whom he met in Switzerland, have a small apartment on the outskirts of Honolulu near Diamond Head. She is a professional contemporary dancer who is currently working part-time. While Hawaii has a lot to offer, it is lacking in the arts, said Vinhateiro.

One thing Oahu does not lack is high waves, and Ben and Karuna have become surfing addicts: “We have surfed in Rhode Island, but that’s nothing like it is here.”

The cost of living on Oahu is high, he said, but then local foods are plentiful. “The farmers’ markets are incredible; in some places lines can be 30 people long. There is a tremendous cry for local foods, and Hawaii is one place where you can put together a complete meal with local food.”

Vinhateiro’s job offers a lot of variety with never a dull moment. As for agriculture, he notes that contrary to widespread perception, there are not a lot of pineapple fields on Oahu and sugar cane is not grown there. Rather there are a large variety of vegetable farms, “they can even grow kale here,” and ranches producing grass-fed cattle.

There is also plenty of aquaculture and hydroponic agriculture. “This is just a great job for me, and we’re both very happy,” Vinhateiro said. “Now it’s just a matter of us convincing our families to visit.”

By Rudi Hempe ’62

Home

Home Browse

Browse Close

Close Events

Events Maps

Maps Email

Email Brightspace

Brightspace eCampus

eCampus