Critical Impact

From NFL Player to Dementia Patient

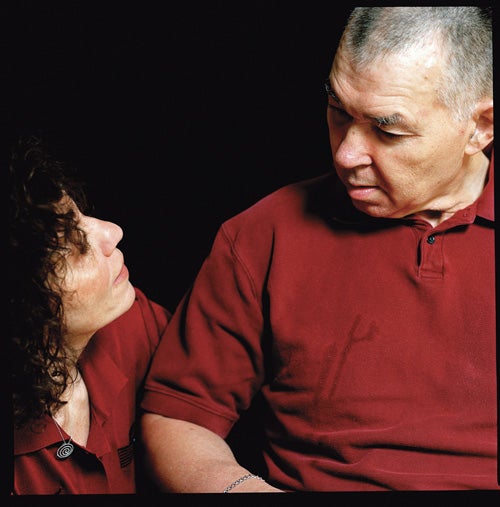

Eleanor Perfetto ’80, M.S. ’88, met her husband, Ralph Wenzel, a physically fit former National Football League offensive lineman, when they were working in South Dakota. “He was healthy, active, and a vegetarian,” said Perfetto, now a senior director of government reimbursement and regulatory affairs for Pfizer, Inc.

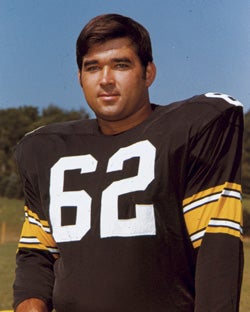

The Johnston, R.I. native had no idea that hidden in her husband’s brain tissue were the beginnings of a chronic disease caused by repeated blows to his head suffered during his football career. Wenzel’s NFL career as a 260-pound lineman ended in 1974 after stints with the Pittsburgh Steelers, San Diego Chargers, and St. Louis Cardinals.

The Johnston, R.I. native had no idea that hidden in her husband’s brain tissue were the beginnings of a chronic disease caused by repeated blows to his head suffered during his football career. Wenzel’s NFL career as a 260-pound lineman ended in 1974 after stints with the Pittsburgh Steelers, San Diego Chargers, and St. Louis Cardinals.

“When I graduated from URI in 1980, I was stationed in Pine Ridge, S.D., with the federal Indian Health Service, and Ralph had taken a job as a coach and teacher at a local school. That’s where we met.”

Warning Signs of Brain Trauma

Clinical Assistant Nursing Professor John Kenna ’05, who is also an acute care nurse practitioner in the neurological intensive care unit at Rhode Island Hospital, said it’s time to discard the term concussion when discussing brain injury.

“I prefer the term traumatic brain injury with levels of mild, moderate, and severe because there can be injury even from a mild blow,” said Kenna, who earned his nurse practitioner master’s degree from Northeastern University.

“The brain floats in fluid, and when there is rapid acceleration/deceleration—as occurs in a violent collision—the brain hits the front and back of the skull. Even with mild traumatic brain injury there can be acute symptoms such as memory loss. With brain injury, a person can have contusions and structures of the brain can be disturbed. Sometimes these symptoms don’t show up for several days or weeks.”

Kenna said parents, coaches, trainers, and athletes should use the following questions/observations when assessing a player for brain injury:

Is the player disoriented? Does he know his name? What day it is?

Is the player experiencing headaches and nausea, or is she vomiting without nausea? Kenna said vomiting without nausea is a major warning sign because it points to pressure in the brain that can spark the vomiting response.

After the incident, does the player exhibit changes in behavior, irritability? If a normally happy-go-lucky person becomes sad, depressed, or overly emotional, those are warning signs of brain injury.

Does the player exhibit any neurological changes, which are indicated by changes in speech and vision?

Is there blood or fluid being discharged from the nose or ears? Kenna said if fluid is being discharged, it is probably from the brain.

Are there changes in the player’s breathing patterns?”

They moved to Rhode Island in the mid-1980s, where Perfetto completed her master’s degree in pharmacy in 1988, and Wenzel served as a volunteer coach for the Rams. In the 1990s, Wenzel, then only in his 50s, began experiencing memory problems and issues with decision-making. His brain function slowly worsened.

Today, because of chronic traumatic encephalopathy, a degenerative brain disease that results in behaviors similar to Alzheimer’s disease, the 160-pound, 68-year-old Wenzel is now in a locked nursing facility, is fed pureed foods, suffers from behavioral outbursts, and is experiencing physical decline from the illness. He no longer understands simple verbal commands.

Wenzel’s condition and the plight of other former NFL players like John Mackey, a Pro Football Hall of Fame inductee who suffered from dementia and died in July at age 69, have led to heavy media coverage of concussions and sub-concussive blows in sports and their connection to chronic brain disease. Sub-concussive trauma is defined as brain trauma that does not produce acute clinical symptoms. It is believed that sub-concussive blows contribute to the development of chronic traumatic encephalopathy.

Perfetto has been an advocate for her husband and other stricken former professional football players. She serves as a board member of the Sports Legacy Institute in Boston, which was founded in 2007 to address growing research showing that sports-related concussions and brain trauma have become a grave health crisis.

NFL management and players’ union officials also know her well. In December 2008, she tried to attend a meeting in Bethesda, Md., between Commissioner Roger Goodell and former players to discuss long-term care. Goodell and others prohibited her from attending. Perfetto’s unsuccessful standoff with Goodell was reported in The New York Times.

“The NFL has been very hesitant, very negligent,” said Perfetto, who now lives in Annapolis, Md. “They long ago accepted that former players with chronic knee, back, and shoulder problems qualify for long-term disability benefits, but they stalled in acknowledging chronic brain injury and dementia as long-term disabilities.

“I don’t think I am on Roger Goodell’s Christmas card list, but that was a good night because I confronted him personally,” Perfetto said. “There has to be greater effort in reaching out to current NFL players, as well as younger players, to convey that this is a serious issue.”

Last season, the NFL got tougher on players who commit helmet-to-helmet hits, and it’s helping states around the country develop laws to protect young athletes from the long-term effects of head injuries. This season, NFL doctors and trainers are using standardized sideline tests for the first time to assess concussions, and they will add a balance test to others used in follow up examinations.

Attention to Head Injuries at URI

Concussions among student-athletes have been a priority for many years. Kim Bissonnette ’77, associate director of athletics for health and performance, said that the National Collegiate Athletic Association, URI, the various conferences, and state associations have all done a great deal in the last several years to educate student-athletes and coaches about the short- and long-term effects of concussions and head injuries. Last fall, Bissonnette completed his 20th season at URI; he has worked in excess of 200 Rams football games.

“We have always taken concussions and head injuries very seriously at URI,” said Bissonnette, who earned his master’s degree in physical education and athletic training in 1997 at the University of Arizona. “We must keep in mind that we are dealing with someone’s son or daughter and that we are talking about brain injury and someone’s long-term quality of life.”

Bissonnette said every student-athlete at URI has to read and sign an NCAA information sheet reminding them of the critical nature of concussions. Bissonnette added that the intense research into short- and long-term effects of concussions, improving technology, and strong education efforts have made many old evaluation standards obsolete.

“For years the gold standard in evaluating concussions was the CAT scan, but we now know that in most cases objective evidence of concussion never shows up on the scan. The feeling was if the CAT scan was OK and the player felt OK, then he could play. Fortunately, the return-to-play standards are now much more stringent,” Bissonnette said.

URI follows a step-by-step approach before it allows a student-athlete to play after a concussion. There is a full assessment and monitoring of a player’s symptoms, cognitive testing, balance testing, and gradual increases in activity once a player is symptom free. If at any point during the process a player’s symptoms return, then the process begins all over again, starting with rest, before the player can be cleared to play.

Bissonnette said the concept of rest after a concussion or head injury should be reassessed as well. “Rest may not just mean staying off the field. It might mean staying out of class because studies put a strain on the brain. It might mean that the player does not go to an away game because sleeping in hotels and early wakeup calls may not be conducive to recovery. It may be best for that person to stay home.”

Training Helps Save Life at South Kingstown High School

South Kingstown High School Athletic Director Terry Lynch ’84, a former player and coach for the Rhody Rams football team, knows that concussion and head injury education probably prevented the death of Mike Gray, a South Kingstown football player, in 2010.

“Mike had taken a couple of hits in the same practice, and after the second one resulted in his head hitting the ground, coach Eric Anderson knew quickly that Mike was in trouble. He called 911 right away,” said Lynch, who oversees 26 head coaches.

The hit caused a subdural hematoma, a mass of clotted blood in the brain resulting from a broken blood vessel, which then led to several surgeries. “Thanks to the quick response by Anderson and emergency medical personnel, we were celebrating Mike’s graduation this year instead of grieving the loss of one of our own,” Lynch said.

Lynch, who is also the color analyst for Rhody radio football broadcasts, said the Rhode Island Interscholastic League and districts like South Kingstown have made head injury prevention and awareness priorities: “Each coach in the state has to be educated on concussions and pass a test to be certified.

“Also, for the 2010–2011 academic year, South Kingstown High School began cognitive baseline testing for football and hockey players. This year, we are expanding the testing to girls’ and boys’ soccer. That means every player on the team takes a cognitive test on a computer. If a player suffers a concussion, we wait until the symptoms end, and then the athlete takes the test again. We compare those results to the baseline results. Our trainer then evaluates the player and all the health and cognitive data to determine the next steps.”

Resisting the Message

While major efforts have been made to address the effects of concussion and brain trauma in sports, Perfetto said most current players don’t grasp the impact of chronic brain illness: “They also have to understand that it’s not only concussions that cause long-term problems.

“Sub-concussive trauma is also linked to long-term brain issues. Many coaches want to make us think that the post-concussion protocols are the solution, but they may give a false sense of security. Repeated blows to the head with no concussion may be more of a problem.

“I have invited current NFL players and their wives to come visit my husband, but I haven’t had one single person take me up on that. I hear the players say they need to make enough money to take care of their families, but do they want to suffer like this, do they want to put their wives, their families through this?

“People talk about rule changes and equipment changes to make the game safer. There is no helmet that prevents the dangerous jostling that happens to a brain when the head receives a blow. It’s like these players are being exposed to shaken baby syndrome every week.”

By Dave Lavallee ’79, M.P.A. ’87

Home

Home Browse

Browse Close

Close Events

Events Maps

Maps Email

Email Brightspace

Brightspace eCampus

eCampus