Getting Technical on Crime

URI is a leader in cyber security research and education.

The technological changes happening at warp speed in the Internet Age have our heads spinning, but bad guys of one stripe or another—from hackers to terrorists—seem to know how to control the spin. That leaves experts on the right side of the law to figure out how to stay ahead of them, and several URI professors are in the forefront of that effort.

Last April, URI received the distinction of being named a National Center of Academic Excellence in Information Assurance Education, thanks mostly to the groundbreaking work of professors in computer science and electrical engineering. The citation, which comes from the National Security Agency and the Department of Homeland Security, marks URI as a leader and innovator in digital forensics and cyber security, and it opens the door for federal funding for research, education, and service. The University is one of only 114 schools so recognized.

The distinction culminates what could be the first round of development at URI in the digital forensics and cyber security arenas. It all began in 2004 when the Department of Computer Science established its Digital Forensics Center, thanks to the foundational work of Professor Victor Fay-Wolfe. Since then, URI has hosted two national cyber security symposia, attracted over $1 million in research grants, and created a growing program in cyber security instruction, including a minor in Digital Forensics and Cyber Security, as well as two graduate certificates involving four- to-five-course sequences.

“It’s just the beginning for us,” says Fay-Wolfe, a recognized expert in digital forensics. “We want to continue to grow our program. We’re developing new courses and eventually new degrees. The field is really taking off, and we are in a good position to be a leader.”

The Digital Forensics and Cyber Security Center has what Fay-Wolfe calls three prongs: education, research, and service. He and his staff have consulted for and helped train the Rhode Island State Police and, in fact, built the digital forensics computer lab where police investigate cyber evidence of crimes ranging from child pornography to financial fraud. The center does consulting work for other police departments in the state, and is involved with the state’s Cyber Disruption Team, which Fay-Wolfe says has developed a strong plan to deal with network disruption as part of the state’s Emergency Management Plan.

“We’re actually ahead of the rest of the country with this,” Fay-Wolfe says. “We want to bring in more partners. This designation as a National Center for Excellence provides us with more credibility, and it will help create more opportunities for research funds. It will also help us recruit top students who are interested in this field.”

The research done by Fay-Wolfe, his associate in computer science Lisa DiPippo, M.S. ’92, Ph.D. ’95, and Electrical Engineering Professors Yan Sun and Haibo He informs the educational and service functions of the Digital Forensics and Cyber Security Center. They have worked on software detection programs as well as emergency response systems, among other tasks. Part of their job, often tied to specific grants, is to come up with new detection products that they then turn over to commercial entities.

“Part of what we do is help investigators learn how to acquire and analyze digital evidence,” Fay-Wolfe said. “It can be something as basic as the procedure for seizing the evidence or how to create protected passwords.”

DiPippo, who was a student of Fay-Wolfe’s several years ago, had worked with Yan Sun on wireless sensor networks, and after the first Cyber Security Symposium at URI in early 2011, she and Fay-Wolfe teamed up again to expand the Digital Forensics Center to broadly include cyber security. “Having Lisa on staff helped us expand into areas that address protecting computer networks,” Fay-Wolfe said. “Yan Sun and Haibo He have done a lot of work on protection of the U.S. power grid and prevention of infiltration of the grid that could disrupt power all over the country.”

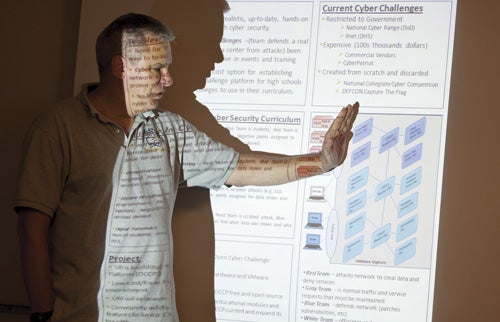

Soon they began to develop courses in cyber security, which they began offering last spring. DiPippo said URI’s center will provide a great benefit to the state because there is a serious need for trained computer scientists. “The jobs are out there, more jobs than there are qualified people,” she said. “There is a big need. Every day we see an article somewhere about a new kind of cyber attack, and we need smart people to help solve these problems.

“A lot of what we do involves finding issues that practitioners are having and creating programs that make their job easier. Through classroom work and research, for instance, our staff and interns were able to determine that police needed assistance with entering search terms as they conducted investigations.”

A relatively new area of research being pursued at URI’s center involves something called steganography, a technique of hiding messages in plain sight. Fay-Wolfe said Al Qaeda has used it extensively to send messages to terrorist cells. To avoid detection of encryption, the messages are embedded in bits inside a harmless-looking photo of a landscape, a building, or a family. Criminals will hide credit card numbers and personal identification numbers in this way, and the Department of Justice is funding research on software programs that learn the steganography so they can detect the difference between a normal photo and one that contains an embedded message.

“These are challenges, but they are critically important to security,” Fay-Wolfe said. “We want to be on the forefront of this research.”

Forming the Digital Forensics and Cyber Security Center has happened in a serendipitous way, as Fay-Wolfe explains. In early 2000 he was looking for some new research areas after years of work on military computer systems. He visited a firm in Washington, D.C., owned by his cousin, where digital forensics work was taking place: “I found it interesting and I thought our students would, too,” he says.

Fay-Wolfe wrote a National Science Foundation grant application to establish the center, and NSF funded it to the tune of $300,000. A year or so later, two more grants came through from the Department of Justice totaling $600,000 to research detection of child pornography. The center’s staff developed programs to measure images in minute detail to determine if the person in the image is a child.

“We can scan website images and determine facial dimensions, high concentrations of skin tones, edges of limbs,” Fay-Wolfe explained. “These are measurable ways to detect if a person in an image is a child. That work, and other research we have done, comes from our strengths as a three-pronged program of education, research, and service.

“When we were consulting for the State Police, we were able to find problems they were having in investigations and detection, and that informed our research. We went to the Department of Justice in an open solicitation bid and they funded our research and we produced a tool to help in detection.”

More serendipity occurred when a URI alumnus, Dan Dickerman ’92, attended a criminal forensics lecture on campus. He had been the lead trainer at the federal Law Enforcement Training Center and had developed the digital forensics training curriculum for the FBI, Secret Service, and U.S. Customs. When Fay-Wolfe discovered Dickerman was a URI graduate and lived in nearby Charlestown, R.I., he asked him if he’d be interested in teaching a course. Dickerman not only agreed, he also helped develop the digital forensics curriculum, one of the first in the country and the only one in a department of computer science.

Because of the Digital Forensics and Cyber Security Center, URI attracted the attention of Rhode Island Congressman James Langevin, who co-founded the Congressional Cyber Security Caucus. He proposed that URI host national experts and leaders in the field for a symposium addressing current problems, research, and future challenges. Langevin has promoted URI in Washington; as a result, last March URI President David Dooley was named by DHS Secretary Janet Napolitano to an academic panel to address national security issues. He is one of 19 members of the Homeland Security Academic Advisory Council.

“URI’s new status [as a Center of Academic Excellence]…will attract more of the best and brightest minds in the field to our state, “Langevin said, “and further demonstrates the University’s commitment to giving our next generation of workers the tools they need to succeed in the 21st century economy.”

Fay-Wolfe and his staff understand the position they’re in, and they are hoping for additional support to grow the program. Staying ahead of terrorists and criminals requires trained staff and research funds. “Resources are crucial to this, and everything is running so fast that as soon you solve one problem, another one appears,” he said. “Things change all the time. We have to be able to stay on top of the changes.”

By John Pantalone ’71

Home

Home Browse

Browse Close

Close Events

Events Maps

Maps Email

Email Brightspace

Brightspace eCampus

eCampus