Harvesting Blue Gold

Restaurant-Ready Mussels, Oysters, and Clams shipped daily!

Maybe you still can’t make a silk purse out of a sow’s ear, but Bill Silkes, M.S. ’80 came close to disproving that adage when several years ago he and others took a disparaged, low form of marine life and made it into a multi-million dollar business.

Silkes is the owner of American Mussel Harvesters, Inc., reportedly one of the largest shellfish companies on the East Coast. The company was forged out of close bonds with URI that started in 1980 when Silkes graduated from the aquaculture program. The interaction continues to this day.

Silkes is the owner of American Mussel Harvesters, Inc., reportedly one of the largest shellfish companies on the East Coast. The company was forged out of close bonds with URI that started in 1980 when Silkes graduated from the aquaculture program. The interaction continues to this day.

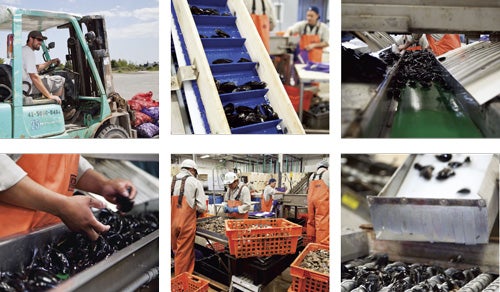

American Mussel Harvesters, which occupies a sprawling building on the shoreline of the Quonset Business Park, leases scores of acres of Narragansett Bay for some of its operations, employs 40 full-time workers, and processes and ships tons of mussels, oysters, and clams around the country and into Canada. Today the firm is poised for a potential market venture that could help remove the Northeast from its economic doldrums.

But the bloom that glows over the mussel industry wasn’t there when Silkes went to Maine to help set up a demonstration mussel farm as part of a Sea Grant project at the University of Maine. Up until that time, the mussel industry did not exist in the U.S. even though mussels were a long-established culinary delight in Europe, gracing the menus of the finest restaurants.

Over on this side of the pond, mussels had a bad reputation—or more accurately, no rep at all. Recalls Silkes about describing the virtues of mussels on his first food show appearance: “I had this big burly guy come up and he ate one. Then he dove in and after downing about 50 he came up for air and said ‘back home we use these for bait.’ That was where the market was at that time.”

The mussel industry needed a jump start, and it got it when a Harvard administrator, Graham Hurlburt, and his wife, an accomplished chef, went to Europe and checked into the mussel aquaculture industry there. They were friendly with Julia Child, who used mussels extensively in her recipes. When the Hurlburts returned to the States they were convinced mussel farming would succeed here. Silkes met the couple while he was in Maine, and they brought him down to Middletown, R.I., to help get Blue Gold Sea Farms established. While he was at Blue Gold, Silkes earned his master’s from URI.

The Middletown start-up was a tremendous amount of work, recalls Silkes. At times he worked two days straight without a break, and the money wasn’t good since the market was in its infancy. Selling mussels was difficult. He relates that one time he decided to make a pitch to vendors at the famous Fulton Fish Market in New York. He bought a suit and went down “but nobody wanted to talk to me. They thought I was the government.” The next day he went to his in-laws’ house on Long Island and changed into his dungarees. He went back to Fulton “and everybody talked to me.”

But by then he says, “I was just burned out, and I did not want anything to do with this anymore.” Silkes decided to quit the Middletown operation. But as it turned out his efforts at the sea farm generated a lot of good contacts, and many of those loyal customers did not want him to leave the business.

He bought a 76-foot dragger and refitted it to harvest mussels. At that time there was a huge natural mussel bed off Nantucket that yielded an ample supply. But then the year of “the perfect storm” hit, and after the storm, winds continued to blow from the east all winter long. Then another big winter storm hit and smothered the mussel bed. “At that point I had this boat and nothing to fish for,” recalled Silkes. “I needed to stay in business, so I went up to Maine and found some resources and started working with clams from Narragansett Bay before diversifying into a full line of shellfish.”

Meanwhile the folks behind the Blue Gold Sea Farm had abandoned the site in Middletown, and Silkes heard that fishermen were complaining that they could not fish there because the bottom was strewn with abandoned gear. Sensing an opportunity, he decided to apply to lease the site under new state legislation that encouraged the development of aquaculture in Rhode Island. He figured that since fishermen considered the site undesirable for their use, they would not object to a new aquaculture venture there.

The state granted the lease with the caveat that Silkes clean up the former owners’ debris. He brought in equipment and divers to rid the 20-acre site of leftover gear. He then installed what are called long lines. Attached to the lines, which are stretched and suspended along the surface of the water with floats, are vertical lines that hold plastic cages. The cages attract mussel seed and also offer a place to grow oysters. Mussel seed occurs naturally in nutrient-rich water; oyster seed has to be purchased from a nursery.

Silkes’ American Mussel Harvesters business actually started in his Wakefield, R.I., home. His wife, Barbara, and he comprised the entire company. He and Barbara, who was pregnant with their third son at the time, hired a babysitter to give them time to work on the business. Today, that babysitter, Jane Bugbee, is vice president of the business.

The business grew; by the mid-1990s they had to lease a building in Galilee. Even that became too small, so in 2003 Silkes built the new headquarters/processing building at Quonset. The building is unique in that it has a custom-built re-circulating sea water system involving various filters, including a bio-filter that keeps the shellfish fresh for processing and shipping. Their operations are spread around however, from Salt Water Farms in Middletown, R.I., to long line installations off Martha’s Vineyard and Sakonnet Point, both in conjunction with cooperating fishermen.

The business grew; by the mid-1990s they had to lease a building in Galilee. Even that became too small, so in 2003 Silkes built the new headquarters/processing building at Quonset. The building is unique in that it has a custom-built re-circulating sea water system involving various filters, including a bio-filter that keeps the shellfish fresh for processing and shipping. Their operations are spread around however, from Salt Water Farms in Middletown, R.I., to long line installations off Martha’s Vineyard and Sakonnet Point, both in conjunction with cooperating fishermen.

American Mussel Harvesters is a family business that grosses about $8 million a year. Silkes’ oldest son, Gregory (Fairfield College, business degree) is the manager. His middle son, Adam ’05 (an aquaculture and fisheries technology major) works on the oyster farms and has a trial long line growing mussels in the West Passage of Narragansett Bay. Mason ’11 (also an aquaculture and fisheries technology major) sets up sales efforts at several farmers’ markets around the state and also works at the Matunuck Oyster Farm owned by Perry Raso ’02, M.S. ’07, another URI aquaculture graduate.

The Silkes family has other ties with URI beyond just earning degrees there. They maintain Sea Grant partnerships on research projects and have close dealings with Fisheries, Animal and Veterinary Science faculty members Terry Bradley, M.S. ’80; Mike Rice, and Barry Costa-Pierce, director of the Rhode Island Sea Grant program.

Rice has helped the company with its aquaculture permits, and he notes that Bill Silkes contributed to the formation of the Ocean State Aquaculture Association. Says Rice, “The relationship between URI and American Mussel Harvesters has been a classic in the traditions of Land Grant and Sea Grant mutual cooperation.” The firm often hosts field trips for URI students interested in aquaculture and Silkes is hoping someday to have a couple of internships in place with URI and Johnson & Wales University, which has a renowned culinary school.

Silkes feels the connection with those in the culinary arts is important for growth of the shellfish market. He explains that his smaller trucks deliver shellfish directly to restaurants in Rhode Island, Connecticut, and Massachusetts resulting in valuable direct contact (and feedback) from restaurant chefs.

His firm also ships seafood across the country to some of the best restaurants via their “restaurant ready” operation that uses overnight shipments to places like New York City and Washington, D.C. Silkes sees a bright future for mussel farming in the U.S. Canada has 85 percent of the U.S. market, he notes, but Canada is reaching its capacity. In Canada, shellfish grow slower and with the Canadians reaching a growth peak, “we could really develop a huge industry here—and it’s starting to happen.”

American Mussel Harvesters is more than just a wholesaler of two kinds of mussels. The company also offer 35 kinds of oysters (two are their own and others are obtained through a “hand-shake” network of other farms,) plus various sizes of clams.

Oysters, says Silkes, are very much like fine wine. Their taste varies according to the location where they were raised, and that involves a host of variables such as water temperature, weather, nutrient content of the water, and breeding methods. Silkes and his employees often have blind oyster tastings in the plant, and some people have become quite good at identifying the flavor profiles. “We cook mussels and shuck oysters every day,” he adds.

On the day he was interviewed, Silkes mentioned that “this morning I’m leaving the house and I said to Barb, ‘do you want me to bring home some shellfish?’ and she said ‘Yes, bring home some mussels.’ ”

No problem there—and the price is right.

—By Rudi Hempe ’62

Home

Home Browse

Browse Close

Close Events

Events Maps

Maps Email

Email Brightspace

Brightspace eCampus

eCampus