Lost and Found

Using a 50-year-old technology that’s been reinvented as an archaeological tool, Kate Johnson ’06 digs up the lost farms of New England

Kate Johnson ‘06 has always wondered about forgotten things. As a child growing up in the northern section of Little Compton, R.I., she unearthed treasures long buried in the woods: a rusted wagon wheel, tumbled stone foundations, ancient apple trees. The route from her 1980s subdivision to the school bus stop afforded opportunities to stumble upon the featureless stones of old cemeteries, and the shards of 19th century ceramics glinting in the furrows of a plowed field.

“At an early age, I recognized that our neighborhood had a deeper time component,” she says. “Every day I would see artifacts, and wonder where they came from and whose they were.”

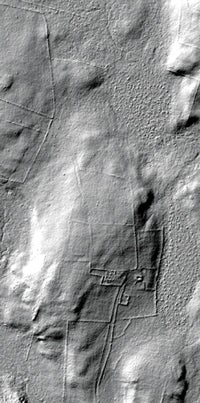

It’s a quest that time and technology have amplified. Today, Johnson explores woods all over New England by air using a method of remote sensing called Lidar, or light radar. The technique pierces the forest canopy with pulses of laser light fired at the earth’s surface at speeds of up to 150,000 miles a second. The reflected bursts yield gray, three-dimensional images in which the telltale grids of former human habitations are easily discerned. Meshed with land records and historical maps, it’s a way to piece together the stories of New England’s lost agrarian past.

In December, Johnson, who double majored in anthropology and art history at URI and is currently a geography Ph.D. student at the University of Connecticut, published a paper with her adviser, Associate Professor William B. Ouimet. Detailing their discoveries about three rural towns, the paper appeared in the Journal of Archaeological Science. That Johnson would see her first scholarly paper accepted by a peer-reviewed professional journal—with first authorship and before she even finished her coursework—seemed miraculous enough. Then the media came calling. In January, National Geographic picked up their story of virtual site excavation. Science and Archaeology magazines, National Public Radio and others followed.

“I was just floored,” she says.

Lidar, invented in the 1960s, shines a small light at a surface and then measures the time it takes to return to its source, creating complex topographical maps. It’s been used by planners, cartographers and geologists for applications as varied as floodplain mapping, earth sciences studies and climate change research. But the data is relatively expensive to obtain and requires written algorithms to identify specific patterns. Archaeologists have been employing the technique only since the 2000s, most famously in the jungles of Belize to detect the ancient Mayan city Caracol.

Johnson and Ouimet were the first to use Lidar to explore land use patterns in New England. Much has changed: European colonists brought English-style farming and the concept of private ownership to the northeast territories, clearing thousands of acres and carving them into parcels bounded by stone walls. Then industrialization in the late 19th century reshaped New England again, drawing population from the countryside to the cities. As families gave up farming, the forests reclaimed their fields, burying the remnants of their homesteads under green briar, pines and maple trees.

The pair accessed publicly available Lidar data of Rhode Island, Connecticut and Massachusetts, collected by the federal Natural Resources Conservation Service and the U.S. Geological Survey. Their 3-D maps of land in Tiverton, R.I., Ashford, Conn., and Westport, Mass., revealed 300-year-old farmsteads, roads, and other sites previously undocumented because they were too remote, or on private property. In Tiverton, for instance, Johnson’s work revealed a dam and the walls of a once-buzzing sawmill. In Ashford, a vast network of roads and stone walls lay buried beneath the canopy of the forest that’s been growing there since the late 1800s. And in Westport, what was equally fascinating was what hadn’t changed. The low stone walls, so ubiquitous and picturesque in rural New England, and the property lines they mark, had in many cases survived centuries of land use untouched.

“It turned out that all of the stone walls matched these 1712 maps,” Johnson says. “It’s pretty incredible when you compare them to modern property maps. It shows this remarkable continuity of landscape divisions that have persisted over time.”

Johnson got her start as a historical geographer at URI, where she took her first archaeological methods course from Anthropology Professor Emeritus William Turnbaugh and blossomed as a scholar under the encouragement of Associate Professor Mary Hollinshead, a classical archaeologist.

She then learned how to use computer generated geospatial datasets, more commonly referred to as Geographic Information Systems (GIS), while earning her master’s degree in historical archaeology at the University of Massachusetts, Boston. Her thesis on the 1690 Wilbor House, home to seven generations of the family and now the Little Compton Historical Society, kept her sequestered in that town hall’s vault, combing through old deeds. She worked for the Massachusetts Historical Commission and the Public Archaeology Lab for a couple of years, refining her digital mapping and spatial analysis skills. But Johnson wanted to continue her studies in a geography program “to truly understand the theory of how humans and environment interact,” she says.

Now the professional journey that began two decades ago in the woods, then moved to the classroom, the town archives, and up to the skies, is returning to the thickets. Johnson and Ouimet will survey some of the sites they identified to validate Lidar’s accuracy in measuring landscape artifacts.

Johnson is also hoping to find the subject of her dissertation somewhere in these forgotten places.

“My heart has always been in New England,” she says. “It’s not always a simple history. And it can end up being imbued with mystical and fantastic qualities that aren’t true. That’s what makes this research so fascinating. There are so many farmsteads out in the middle of the woods. I really want to tell the story of this process of abandonment.”

—Ellen Liberman

Home

Home Browse

Browse Close

Close Events

Events Maps

Maps Email

Email Brightspace

Brightspace eCampus

eCampus