To Give

Yes, we’re a small university, in a state that’s long been popular culture’s byword for “tiny.” Also, perhaps, “provincial.” We all know this, just like we know that URI is pretty much synonymous with oceanography, engineering and nursing, despite its many other excellent programs and niches. And hey, we can share the joke. But we also know these tropes don’t define us.

In fact, altruism and giving back are hallmarks of the University. What follows is a glimpse at the lives of students, staff and alumni who have gone into the world, near and far, and done surprising, selfless, and even dangerous work. Some dedicate their lives to service; others weave volunteer activities into lives busy with other pursuits. Some target the desperate far away; others look closer to home. Thanks to them, we live in a better world. This holiday season, that’s something to cheer.

Lily McKay ’13

is wrapping up a trip to Tanzania right now, where she has been working with the 300 grade-school kids at Saint Timothy’s School while simultaneously trying to raise $20,000 to create a resource center for their teachers. Check out the Saunderstown native’s fundraiser page at classy.org, where McKay has posted videos of the students. “We need someone to save this crazy world,” comments one donor. “Thank goodness there are people like you!”

Rob Maroni ’91

The Syrian refugees flee with nothing. No food. No belongings. What they do carry, they are desperate to unload: horrific memories of a sickening civil war that has created one of the worst humanitarian crises of our time.

Robert Maroni is helping them, one by one. As country director in Jordan for Mercy Corps, a global relief organization, Maroni manages aid programs for 500,000 refugees, including thousands living at refugee camps that provide a home—and some stability.

Three years into a war escalating daily as ISIS ramps up involvement, nearly 190,000 Syrians are dead and another 3 million are scattered throughout the Middle East. On foot at night to evade snipers, many are flooding into Jordan, just across the southern border. Mercy Corps helps run two camps, mini-cities in the desert: Azraq, a haven for 6,000 refugees, and Za’atari, the second-largest refugee camp in the world, with 85,000 people.

Three years into a war escalating daily as ISIS ramps up involvement, nearly 190,000 Syrians are dead and another 3 million are scattered throughout the Middle East. On foot at night to evade snipers, many are flooding into Jordan, just across the southern border. Mercy Corps helps run two camps, mini-cities in the desert: Azraq, a haven for 6,000 refugees, and Za’atari, the second-largest refugee camp in the world, with 85,000 people.

The immediate physical requirements are obvious: shelter, food, clean water. But it’s the emotional needs that are more elusive. Maroni and his team of 200 excel at both, whether it’s improving water supplies and digging wells or showing evening movies and building playgrounds where kids can kick around a soccer ball.

Many of the refugees are battle-scarred children running from what the United Nations human rights chief calls Syria’s “House of Blood.’’

“Their villages have been blown up, their houses destroyed,’’ says Maroni. “They’ve seen people getting shot. They’ve seen death and destruction. They’ve seen the ugly side of humanity.’’

It was in the Peace Corps, as a volunteer in Cameroon, that Warwick, R.I. native Maroni, 50, first felt the pull of human-itarian work. Soon he was in Rwanda, rebuilding villages destroyed by genocide, then Eritrea, where he coordinated an HIV prevention project.

He joined Mercy Corps in 2004, helping children in Zimbabwe orphaned by the country’s HIV epidemic. In 2010, he landed in Jordan, where he lives with his wife, Nadia al-Alawi, and two daughters, ages 11 and 13—and cares for some of the most vulnerable people on the planet.

“The needs here are enormous,’’ Maroni says. Schools are overcrowded. Many refugees don’t have enough clothes; some can’t afford medicine. “These are people like you and me who lived in houses and cities. Now there’s a huge upheaval in their lives for one reason—war.’’

Yet they adjust with courage and hope, he says. At a new gym in Za’atari, Mohammed Al Karad, a refugee and Syria’s 32-year-old national wrestling champion, teaches kids how to box, lift weights, and love life again. “Our gym is full every day,’’ says Maroni. “You can see where your work is making a difference.’’

How long does he expect families to stay at the camps? Up to a staggering 15 years.

Bethany Eisenberg Zeeb, M.S. ’87

Bethany Eisenberg was a nervous wreck a decade ago when she asked family and friends to forgo presents on Christmas and instead donate the unopened contents of their bathroom cabinets.

Bethany Eisenberg was a nervous wreck a decade ago when she asked family and friends to forgo presents on Christmas and instead donate the unopened contents of their bathroom cabinets.

“I didn’t know what to expect,’’ she says.

Eisenberg was floored by the response: Great idea, and where can we put the boxes. The donations—infant Tylenol, diaper cream, vitamins—were packed into even bigger boxes and shipped to a hospital and orphanage in Guatemala that treats the poorest of the poor.

That holiday campaign evolved into the Guatemala Aid Fund, a thriving nonprofit that has raised thousands of dollars to help children in a country where nearly half suffer from malnutrition and 75 percent of the people live below the poverty line.

John Diego, 16, and Joseline, 14 are the two reasons Eisenberg is passionate about the country. She and her husband, Peter, adopted them from Guatemala City when they were babies, and during subsequent visits the harsh poverty the couple saw was wrenching.

“I have to do this,’’ says Eisenberg, 53, who graduated from URI in 1987 with a master’s degree in water resources and works for VHB Inc., an engineering company in Watertown, Mass. “I’m blessed in every way. I have family, friends, job satisfaction, a good education. The poverty in Guatemala is so tremendously worse than here.’’

After the Christmas drive, Eisenberg thought she might be on to something: people would donate to a project that could show tangible results. Eisenberg soon figured out that it was costly to ship items and would be smarter to raise and send cash. Today, the nonprofit gives money to two small orphanages and a program called Happy Hearts that strives to keep fractured families together through counseling. She continues to ship medical supplies to Hermano Pedro Hospital and Orphanage in Antigua.

Donations have an immediate benefit: $2,000 to two-month-old Andres for a hernia operation that saved his life; a refrigerator—the first—for the Luz de Maria orphanage and its 32 children; a yard at the orphanage for children to play tag; and new shoes for dozens of children, thanks to Massachusetts students who participate in Guatemala Aid Fund’s Caring Kids Club.

Teaching young Americans that many children in other countries sleep six to a room on a dirt floor or don’t get new school shoes every year is an important part of the organization’s mission.

“I want children to grow up with a sense of wanting to give and share,’’ she says. “Even if it’s a little bit, they can make a difference. Everyone can.’’

Mike Pinto ‘15

Mike Pinto ‘15

is a mechanical engineering graduate student from Milford, Mass., who practices the Brazilian martial art capoeira. Last summer he managed to find time to raise money for Central Falls’ Children’s Friend organization, which provides services to vulnerable children.

Bryan Watkin ’09

Big foreign aid groups don’t impress Bryan Watkin, especially the one that distributed hundreds of pink harmonicas to children in an African village. “No one even taught them how to play,’’ he says. “It was a waste.’’

Helping Africans survive on their own, without government handouts, is the goal of Watkin’s WearAfrica, which sells handmade African goods by local artisans. Watkin buys most of the products—bracelets, necklaces, tribal masks—directly from the artists so the money goes into their pockets.

“It’s so important to support local businesses in Africa—the Mom and Pop stores,’’ says the 27-year-old Maine resident. “It allows people to empower themselves. I hate the phrase ‘sustainable development’ but that’s what I’m trying to do. They want to be able to support their families, like everyone.’’

The son of a career military officer, Watkin was all set to continue the family tradition by enrolling in West Point when he took a high school course in oceanography. Fish farming became his obsession. After graduating from URI with a bachelor’s degree in aquaculture, he joined the Peace Corps, settling in Kanzala, a village of 1,200 in northwest Zambia. Home was a two-room thatched-roof hut with an outhouse. He had no electricity or running water. “I loved it,’’ he says.

Not only did he teach villagers how to harvest protein-packed fish to feed their families, he came to adore a culture that he says excels in humility and happiness, despite extreme poverty. “I remember listening to kids cry for two months during the hungry season from November through January,’’ he says. “They were eating nothing but nshima,” a porridge made from ground cornmeal.

WearAfrica could put food on their tables.

Watkin returned from the Peace Corps in 2013, unsure about his future. During a trip to South Africa to help start an oyster farm, he visited a city market and was charmed by the handmade crafts. On a whim, he bought some jewelry and sold it on eBay. Sales were so good he decided to buy more and WearAfrica was born.

The items are utterly unique—bracelets of copper or polished cow bone, knives with intricately-carved handles, handbags made with schetenga, a brightly-colored African fabric. In his trips back to Zambia, Watkin tracks down artisans in remote villages after long treks in the bush. One partnership he is especially proud of is with adult Zambians who have physical challenges and make handbags.

Twenty percent of WearAfrica’s profits are donated to locally-managed charities in Africa that help with pressing issues, like clean water and better agricultural practices. Ultimately, Watkin hopes his products inspire people to talk about the wonders of Africa and its people.

“We hear so many negative stories in the media about Africa, and I want to change that,’’ he says. “It’s a beautiful place. I like the Wild West aspect of it. It’s raw, and the people are real. They are who they are and that’s lovely to me.’’

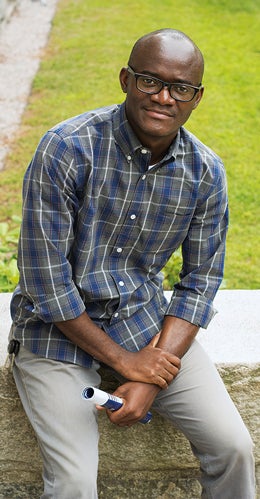

Komlan Soe ’13

Komlan Soe ’13

Growing up in a refugee camp in West Africa, Komlan Soe experienced the humiliation of being contained, like a caged animal. Those memories came flooding back when he saw television images of his fellow Liberians sealed off in their neighborhood by barbed wire in a cruel government action to control the deadly Ebola virus. “Seeing that was heartbreaking,’’ he says. “I knew I had to do something.’’

That urge to help led to the #EbolaBeGone Campaign, a group that he and other Liberians in Rhode Island founded to raise awareness about the disease ravaging Liberia, Guinea, and Sierra Leone. The young men and women—among the 15,000 Liberians in the state—collected and shipped thousands of medical supplies to Liberia in August. Another shipment went out this fall.

“I want to help the helpless,’’ says Soe.

And that includes, at least for now, his mother, brother and sister, who live in Liberia’s capital, Monrovia, where the disease is spreading rapidly. Miraculously, they’re healthy, he says, but terrified of leaving their house. His brother goes out once a day to buy food.

“The country has collapsed—the healthcare system is broken, businesses and schools are closed, bodies are left on the street,’’ says Soe. “People need to know this is not just a Liberian crisis. It’s a global crisis. We need to take action before it’s too late, before millions die.’’

Born in Liberia, Soe fled the country at age 3 during a bloody civil war, ending up in a refugee camp in the Ivory Coast and, later, Ghana. Life behind a fence was bleak. Surviving on rice and canned sardines, he often went to bed hungry. Home was a shack. His classroom was the dusty earth under an acacia tree.

A move as a teenager with some of his siblings to Rhode Island provided opportunities he had only dreamed of as a boy. Last year, the 27-year-old Providence resident earned a bachelor’s degree in political science, the first in his family to attend college. Graduate school will come, but first his homeland.

“The most vulnerable people in the country are dying,’’ he says. “I believe in giving them a voice.’’

Sara Stevens Nerone ’90, M.S. ’95

Sara Stevens Nerone ’90, M.S. ’95

Sara Stevens Nerone brought violins and Bach to Vietnamese children who could barely afford shoes, much less a musical instrument. She taught them how to paint with watercolors, and she provided shiny new bicycles to girls so they could ride, not walk, the 10-mile journey to school.

Through her nonprofit, Rock-Paper-Scissors Children’s Fund, Nerone—who earned a master’s degree in wildlife and a bachelor’s degree in anthropology from URI—has touched the lives of 500 Vietnamese children, many so poor their parents make less than one dollar a day. “There’s no way I could not do something,’’ she says.

Nerone’s journey to kindness started when she and her husband, Christopher Nerone, a renowned botanist at URI who died in 2010, adopted two girls from Vietnam: Sophie, now 16, and Phoebe, now 13. Two years ago, Nerone, 52, returned to the country with her children and partner, Patrick O’Brien, to volunteer.

Back home in Wakefield, she knew what she had to do: give.

So far, she’s raised nearly $60,000 to pay for bikes for children in Khanh Hoa Province, and art and music programs in Cam Duc Village, a poor town in central Vietnam.

The arts programs give the kids a place to gather away from the grinding poverty. They play Bach minuets on violins provided by the nonprofit. They draw and paint in classes that emphasize free expression. Last summer, the nonprofit held three-day music and art camps in ethnic minority villages.

The bike program, exclusively for girls, is keeping them in school. Many drop out because their walk to school is too long—three hours in some cases. Now, nearly 300 girls have new bikes, thanks to Nerone and her daughters, also tireless volunteers.

“I want my daughters to know the Vietnamese culture,’’ says Nerone, an ecologist with the National Park Service. “I also want them to know how important it is to give back.’’

Goodness runs in the family. Phoebe helped with a campaign at her middle school to collect donations for elderly men and women in Cam Duc. There were smiles all around when they received their gift: 350 pairs of reading glasses.

Dianne Fonseca ’70

“Keeping the Pace with Dianne” is Rhode Island’s top fundraising team in the American Cancer Society’s (ACS) annual Making Strides Against Breast Cancer walk —and, impressively, one of the top 20 in the United States.

“Keeping the Pace with Dianne” is Rhode Island’s top fundraising team in the American Cancer Society’s (ACS) annual Making Strides Against Breast Cancer walk —and, impressively, one of the top 20 in the United States.

So it is no surprise that keeping pace with Dianne Pastore Fonseca ’70, a 15-year breast cancer survivor, is not easy. Raising more than $150,000 to date, Fonseca, with the help of family and friends, is constantly striving to do more in the battle against this deadly disease. She raises not only dollars, but critical awareness, through events like a celebration of survivorship, where more than 300 women came together at a local country club; Zumba nights; pig roasts; and Pink Outs, pink ribbon card sales, and faculty dress-down days at local schools. Fonseca received an award for her extraordinary volunteerism from the New England division of the ACS last June. And as she says, “more events are in the works.”

Michael Rosati ’73

When the devastating tsunami of 2005 struck Indonesia, Michael J. Rosati, a consultant who has lived in Thailand since 2001, traveled to the region to see what he could do to help its youngest survivors. Rosati, who has worked for the United Nations and whose career has included stints as a senior technical expert at the Thailand Ministry of Public Health, senior scientist at Education Development Center, and senior advisor to the Pacific Institute for Research and Evaluation, was not focused on what these young people had lost. Visiting an island where more than 350,000 had been killed by the tsunami, Rosati worked to empower survivors by providing them with tools they could use in disaster preparedness going forward. A week-long meeting sponsored by the Thailand Ministry of Public Health in partnership with several NGOs including UNICEF, drew participants from Indonesia, Pakistan, and Thailand, who then returned to their communities to work with local NGOs to prepare other young people to face similar disasters. Rosati definitely subscribes to the “teach a man to fish” axiom.

Rosati is a renaissance man of the helping professions. His broad-ranging career has focused on promoting mental health among young people; addressing issues of substance abuse and HIV/AIDS; promoting participatory learning and skills development in classroom settings; developing multimedia for instructional purposes; involving young people in disaster preparedness; and designing social marketing campaigns that address a wide range of health and social issues.

A native of Providence, he has fond memories of his years at URI, and credits Professor Chris Heisler in the School of Education with influencing his decision to make education part of his life’s work. “Heisler was an extraordinary man, a veteran of WWII, like my dad, and he always impressed me with his humanity and wisdom,” he recalls.

Rosati’s move to Thailand came after the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services asked him to advise the Thai government on various aspects of health promotion including strategic planning and social marketing. His clients have included UNESCO, the World Health Organization, Catholic Relief Services, Dong Tam Drug Recovery Center in Vietnam, and numerous other agencies and schools throughout Southeast Asia.

– By Elizabeth Rau, Melanie Coon, and Pippa Jack

Home

Home Browse

Browse Close

Close Events

Events Maps

Maps Email

Email Brightspace

Brightspace eCampus

eCampus