Writing the Book on Ponzi’s Scheme

When Bernard Madoff was arrested and charged with swindling investors out of $65 billion, the news media described the swindle as “the biggest Ponzi scheme in history”; however, the man for whom the scheme was named might have taken umbrage at the description. In his curious manner of thinking, Charles Ponzi would have seen Madoff for what he was, a ruthless swindler, whereas he thought of himself as a virtuous risk-taker.

When Bernard Madoff was arrested and charged with swindling investors out of $65 billion, the news media described the swindle as “the biggest Ponzi scheme in history”; however, the man for whom the scheme was named might have taken umbrage at the description. In his curious manner of thinking, Charles Ponzi would have seen Madoff for what he was, a ruthless swindler, whereas he thought of himself as a virtuous risk-taker.

The meltdown of the American economy last summer smoked Madoff out of his palatial hole and into the public psyche. As the story was breaking, URI alumnus Mitchell Zuckoff ’83 became a prime source on the history of Ponzi schemes. Though most people were familiar with the term, few knew its origins or the story of the man behind it. Zuckoff has discussed Ponzi and the contemporary version of his famous scheme on the CBS Evening News, National Public Radio, and PBS’s Frontline, and in The New York Times and other newspapers.

A former special projects reporter at The Boston Globe and a Pulitzer Prize finalist for investigative reporting, Zuckoff has written the book on Charles Ponzi—literally. Ponzi’s Scheme: The True Story of a Financial Legend, Zuckoff’s 2005 account of Ponzi’s life, reveals not just the origins of that infamous scam, but the amazing personality behind it. The colorful story set in Boston, filled with scoundrels and innocent but often greedy victims, banking scalawags, and corrupt politicians, might make a great film someday. It could even make it to Broadway as Zuckoff, who teaches investigative journalism at Boston University, has sold both the film and stage rights.

The timing certainly seems perfect. “We’re seeing a lot of Ponzi-like schemes unveiled now,” Zuckoff said in a recent interview, “from Enron to Bernard Madoff and others. When the tide goes out, the rocks show up.

The timing certainly seems perfect. “We’re seeing a lot of Ponzi-like schemes unveiled now,” Zuckoff said in a recent interview, “from Enron to Bernard Madoff and others. When the tide goes out, the rocks show up.

“Once I started working on the book, I thought it would make an interesting movie. The arc of the story is so interesting, and there are great characters. Ponzi was much more complex than just being a crook and a swindler. Even the prosecutors were interesting with their unsavory backgrounds.”

An Italian immigrant who came to the United States in the early 20th century to make his fortune, Charles Ponzi was intent on redeeming himself in the eyes of his mother after he squandered the money his family had given him for college. Not unlike a variety of swindlers today, he rose on a rising tide that marked the live-fast-and get-rich-quick Roaring Twenties, a tide that hadn’t receded months later when his “robbing Peter to pay Paul” scheme collapsed.

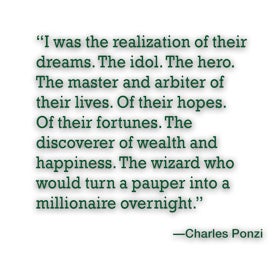

Clever, charming, and charismatic, Ponzi drifted from one odd job to another but always seemed to be attracted to get-rich-quick schemes. He served jail sentences for shady behavior in Montreal and for helping fellow Italians cross the border from Canada into the United States. He landed in Boston, where his whirlwind success made him famous. He used his charm and wit to portray himself as a man of the people, a scamp more than a scoundrel.

Clever, charming, and charismatic, Ponzi drifted from one odd job to another but always seemed to be attracted to get-rich-quick schemes. He served jail sentences for shady behavior in Montreal and for helping fellow Italians cross the border from Canada into the United States. He landed in Boston, where his whirlwind success made him famous. He used his charm and wit to portray himself as a man of the people, a scamp more than a scoundrel.

While trying to build a legitimate business, Ponzi stumbled upon a plan to attract money for a company that would invest in International Reply Coupons, a convenient form of reply postage used by many immigrants sending mail to the old country. Beginning in the fall of 1919, he started taking small amounts of money from investors, many of them immigrants, who were sold on the idea by his enthusiasm. Before too long he was raking in more cash than he could keep track of. Within months people were turning over thousands a day. By July 1920, he estimated his net worth at close to $15 million.

But it was a proverbial house of cards built on phony investment. Ponzi had promised investors a 50 percent return in 45 days. Like Madoff, he invested very little of the money. As long as people kept turning over their investments, he was safe. Once they started calling in their money—just as Madoff’s investors did nearly a century later—Ponzi would run out of cash to pay them.

As Ponzi amassed his wealth, he encircled himself and his family with its trappings, including a Lexington mansion, an expensive car, fashionable clothes, jewelry, and art. But the heat was on from The Boston Post, the city’s most read newspaper, and investigators at the city, state, and federal levels.

Ironically, the boldly confident Ponzi invited investigators to examine his operation. Although he almost got away with it, Ponzi’s scheme was doomed. By August 1920 he was in jail. He would eventually spend more than 10 years in prison and be deported to Italy, living most of the rest of his life in a hand-to-mouth existence.

How did Zuckoff get into the neglected story of this wily swindler? Like most reporters, Zuckoff is always on the lookout for a good story. While he was a banking reporter at The Boston Globe during the credit union crisis of the early ’90s, someone mentioned that Boston hadn’t seen so many banks close since Ponzi’s day. Zuckoff had no idea Ponzi’s scheme was launched in Boston. He began filing away items pertaining to Ponzi, and when the dot.com bubble burst in the late ’90s he started working on the book, uncovering Ponzi’s long ignored autobiography and a treasure trove of newspaper accounts, records in public archives, and family papers and letters.

“I was astonished at what I found, especially in the archives,” Zuckoff said. “The records were still wrapped in string as if they had been put away and never touched.”

A native of Bellmore, Long Island, Zuckoff chose URI because of its journalism program. He credits the late Wilbur Doctor, who taught at URI for two decades, with guiding him into a career as an investigative journalist. Zuckoff acknowledges Doctor’s contribution to Ponzi’s Scheme; the professor read the manuscript not long before his death in 2008.

There’s no point in asking if a Ponzi scheme could take place today, as Madoff sadly proves. But Zuckoff does offer that the 2009 economic meltdown has everything to do with a lack of vigilance by regulators. “These things were right under their noses,” he said. “The tools are in place at the Securities and Exchange Commission, but they seem to be better at handling insider trading cases and dealing with specific complaints. They didn’t seem interested in other cases. This doesn’t diminish Madoff’s culpability, but they [SEC regulators] let him do what he did.”

By John Pantalone ’71

Home

Home Browse

Browse Close

Close Events

Events Maps

Maps Email

Email Brightspace

Brightspace eCampus

eCampus