A Passage to India

The incredible, tragic, wondrous story of Laurie Rockwell Sharma ’92, who once struggled to find a reason for living, and of the families she lost, the families she found, and the families she is making now.

By Marybeth Reilly-McGreen

The two sobbing boys, naked but for a scrim of grime, wrapped their arms and legs around Laurie Rockwell Sharma ’92 and held fast. “One was maybe a year old and the other, maybe 3. And they looked up at me with their big brown eyes and they were saying something, and I didn’t know what they were saying,” Laurie remembers. “And I looked down at them and it just broke my heart.”

The year was 2006, and it was Laurie’s first trip to India as the new lead designer at JPC Equestrian, a company that manufactures equestrian clothing and gear. She looked to Varun “Timmy” Sharma, JPC Equestrian’s owner and her future husband, for guidance. “I looked around to see if there was a parent around caring for them. There was nobody. I remember asking Timmy, ‘What is this? Isn’t anybody doing anything about it?’ And he just looked at me and said, ‘No. This is just every day in India.’”

Twenty million of the world’s 100 million street children live in India, a country that is home to one third of the planet’s poor. The toddlers who clung to Laurie were likely already in the thrall of one of the begging gangs for which India is notorious. A foreigner—especially a fair-haired Western lady with kind eyes—was a good mark. To natives, on the other hand, the appearance of the two apparently abandoned, sobbing children sounded no alarms. If anything, the kids were a nuisance, representative of a problem that is both too big and too commonplace. Gangs in India are said to maim children, or place babies in the care of toddlers, to stage more pathetic tableaus. The more pitiable a child can appear, the greater the likelihood of remuneration.

Timmy explains that a childhood in India had left him “jaded, almost dismissive. Her reaction was so unexpected.”

But for Laurie, the horror was new, and real. “I said, ‘Well, somebody has to do something,’” Laurie remembers. “And Timmy looked at me and said, ‘What is one person going to do?’”

The answer arrived on a Sunday afternoon in early 2010, when Timmy and Laurie were hosting a luncheon for JPC Equestrian’s factory employees and their families. Little did they know that three thousand people would show up. While joyous, it was a chaotic event; the attendees had never seen such a feast, and rushed the tables. Timmy and Laurie found themselves preoccupied with their factory workers’ children. “I was seeing all these amazing, adorable kids,” Laurie says. “They had no education. They couldn’t even write their own names.”

“I saw the impact we could have in our own orbit,” Timmy adds. “Typically Indian children end up in the same professions as their parents. But I thought, if the right opportunity presented itself, who knows what could happen?”

The pair made a decision that day. They envisioned a different future for the children, a future with the potential to free them from low-level industrial work—and a chance to escape a thousands-year-old caste system that would otherwise tether them to the fates of their parents.

They would start a school.

But first, the story of the girl who lost her mother. Twice.

Because to understand why Laurie was riven by the sight of those two, abandoned beggar children—and why she and Timmy have now invested $10 million of their own money into their school outside New Delhi—means looking more than 40 years back, and half a world away.

Laurie grew up in Portsmouth, R.I., the third and youngest child of adoptive parents. Her two older sisters were her parents’ biological daughters. Laurie’s parents, the Rockwells, were good people, good providers, but despite that, Laurie felt an otherness. And she felt it keenly. She knew what it was like to be a child alone in the world.

“I was very huggy, touchy-feely, and my parents weren’t,” Laurie says. “I struggled with why I was born. I knew my life had to mean something. From a very young age, I was searching for love and acceptance. I dreamt about my mother’s love and finding her.”

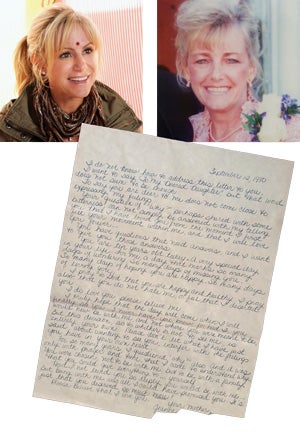

When Laurie’s adoptive mother died in 1999, her adoptive father asked if she wished to find her biological mother. Laurie, then 29, jumped at the chance. There wasn’t much to go on—just the name and phone number of the adoption agency. The woman who answered Laurie’s call wasn’t hopeful. The address she had on file was 30 years old, but she promised to write to see if anyone there could help. And the agency had something else: a letter from Laurie’s mother, Jeanne Robinson. Just a teenager when she got pregnant with Laurie, Robinson had written the letter on Laurie’s tenth birthday, 19 years earlier. It spoke movingly of how she loved and longed for the daughter she had given up.

Laurie was elated. By early 2001, she had an appointment to go to the adoption agency in person. Once there, she learned that Robinson’s ex-husband had responded to the agency’s letter. He recounted how Robinson had gone to her mailbox every day hoping to find a letter from Laurie. But it was too late for a happy ending—Robinson was dead, murdered by her fiancé, Edwin B. Edwards, just a few months earlier. It had happened after the wedding of Robinson’s daughter, a half sister Laurie had never met. “He grabbed a flashlight from the trunk of his car and hit her in the head several times with it. As she fell to the ground, he jumped into his car and reversed it over her body,” Laurie remembers, her voice thick and wobbly. On the day Laurie arrived at the agency and received this news, the Providence Journal’s headline story was that Edwards had been found guilty of first-degree murder. The paper ran a picture of Robinson with the story.

“You look just like your mother,” the lady from the agency said.

But Laurie’s birth mother was gone, again, just as she believed she was finally within reach. In an instant, yearning turned to mourning.

There was some happiness to be had, some coincidences to marvel at. Laurie met her mother’s family, as well as her biological father. “I learned that I’d waited on my grandfather while a cocktail waitress at Christy’s,” she says. “And I was close friends with a guy who turned out to be my cousin.”

Laurie put her tenth birthday letter in a cabinet that used to belong to Robinson. She had that, and Robinson’s photo, and a new family. Those things couldn’t take away the bitterness, but they helped.

And she had her horses.

For as long as Laurie can remember, intertwined with her yearning to find her birth parents was another powerful desire: to ride horses. “It’s something I was born with for sure,” she says. “The bond they have with you, and the love they have—they show it. On top of my Christmas list every year was a pony. I looked for friends who had horses. The smell of a horse was a drug to me.”

She recalls attending the International Jumping Derby in Newport, R.I., when she was nine years old, at the invitation of a friend whose sister was competing. But Laurie’s desire to be the girl in the saddle was so strong that she couldn’t enjoy it—she wept through the event.

Her route to middle school each day took her by a horse farm. She begged the owners to let her clean stalls in return for lessons. They agreed, but Laurie’s mother forbade it. Laurie was crushed. “I had such a passion for it but I just . . . it was like a balloon that just got farther and farther away.”

She wasn’t able to join the equestrian team at URI—she had already committed to soccer, and the two sports shared the same season. But after college, she found a way. A friend at Christy’s had a horse barn and accepted her offer to muck stalls in return for lessons. By 2001, burdened by the preceding year’s deaths—the mother she had known but been unable to connect with, and the mother who had loved her so fiercely but whom she’d never met—she found solace in her old passion. She plunged herself into the equestrian world, competing in, and winning, riding competitions with her horse, Bailey. But the financial pressures were serious. “I had to become an entrepreneur,” she says, “because I knew I had to support her.”

The million-dollar idea came quietly, while she was doing laundry: she decided to embellish her saddle pad with ribbon trim. She bought a sewing machine and taught herself to sew. Her creations soon caught the attention of people at the horse shows, and she found herself taking orders while in the saddle. Encouraged, she founded her company, Equine Couture; the line caught the attention of major companies in the equine industry, among them JPC Equestrian. In 2006, at a trade show, Timmy proposed they merge businesses. In 2010, they started their school; and in 2011, they partnered for life.

They called their school Salvation Tree.

The Sharmas found a small school building to lease and opened the doors in April, 2010. That first year, there were 40 students. A class has been added every year since and by 2015, enrollment had grown to more than 400. The school was outgrowing its home.

So that year, Laurie and Timmy purchased 2.5 acres of land near their factories in Greater Noida, southeast of New Delhi in the northern part of India, and began construction of a 160,000-square-foot facility. In 2017, it welcomed not just the factory workers’ children, who continue to attend for free, but also a new cohort of tuition-paying students.

Salvation Tree is a Christian school in a country that’s 84 percent Hindu, a religion that practitioners call a dharma, or way of life. From the beginning, it was important to Laurie that everyone know the school followed Christian values, even though they might sometimes be at odds with deeply embedded aspects of Hindu life. That became especially true for the new, wealthier families. The mixing of social classes that happens in Salvation Tree’s schoolrooms isn’t often seen in India, and some tuition-paying parents initially complained.

Laurie asked to address them: “I told them how God had blessed us and that because of that, we’re here to impact your lives and your children’s lives. I said we believe God created us all as equals, which is why we don’t believe in the caste system.”

She got a standing ovation. There were no further complaints. “It was like they were starving for someone to stand up for what’s right,” Laurie says. “There have been a thousand tremendous moments like that.”

There have been plenty of moments of frustration, too.

Laurie and Timmy have promised to educate their employees’ children through high school, and then pay for university elsewhere. While it’s a significant financial commitment, the university bill won’t be too staggering: Only four of the original class remains. The rest were pulled out of school by their parents to take care of younger siblings, or to go to work to help support the family. Laurie pleaded with the parents of one particularly gifted girl to allow her to stay in class, but failed to change their minds. “It breaks your heart,” she says.

Poverty and sexual discrimination have a symbiotic relationship in India. Female children are often excluded from the opportunities offered to their brothers. Sometimes, in fact, they are denied life itself—illegal gender tests are popular and female infanticide is widespread, according to The Borgen Project, a humanitarian organization that monitors global poverty. The British Medical Journal contends that 12 million Indian girls have been aborted in the last 30 years.

Vaibhav Kapoor has a vision of a different India, one in which his daughter is an educated professional. “As a parent, I want the best for her,” he says. “Whatever she decides to do, we would help her to pursue that.”

Kapoor’s daughter attended a different fee-paying school before moving to Salvation Tree. He credits the Sharmas with “great thought and vision. This is definitely something that is needed in our society. Education is the backbone of any country.”

JPC employee Mukesh Jha, whose children are the beneficiaries of a free education, calls the opportunity life-changing. “My kids are doing very good in school and by the right education they will become independent and confident in their life,” he says. “As I got this opportunity, so I am confident enough that my kids will certainly do better in their life. This is the best virtue for my kids and me.”

The new school building is still under construction, and won’t be finished until 2020. At that point, it will have the capacity for 2,000 students, and the Sharmas expect to fill it.

While this is a happy ending, it is no fairytale.

“When you go to India, there’s lots of smog. The sky isn’t that blue. And it’s hard to see all these kids and families on the side of the road with nothing,” ParisElla says. “Literally nothing. But they still have smiles on their faces.”

ParisElla intends to run the school someday—and be a pediatrician. She’s 11, and anything is possible. She’s already been to India more than a dozen times and loves it. Like Laurie, she would like to live there one day.

India takes its toll on the body and the spirit. But the dust that’s so thick it’s hard to breathe, the smells that sting the eyes and nose—these can be endured. Much harder for Laurie are the tragedies she’s been made a part of. There was the woman who thrust her child at Laurie pleading, “Please take my child to America.” There was the man who dragged himself towards her, his arms doing the work of missing legs, begging for something, anything, money, food, water. It was summer in India and the temperature was 120 degrees—at night. Tires had melted into the pavement that day.

“I thought, ‘This is hell on earth.’ I just wanted to bring him into my house and give him a bath and a bed,” Laurie remembers.

“And then what?” Timmy had asked her.

She had to content herself with giving him a bunch of bananas.

Hardest of all to bear might be the girl who lingers outside Laurie’s home in India. Bindia, maybe 15, last name unknown, routinely stands outside Laurie’s house peddling necklaces. Day in, day out, Bindia’s been doing this since she was a toddler. She makes a lovely presentation, with her very proper: “Hi, ma’am. How are you today?”

Over the years, Laurie has seen Bindia harden, getting into fights with other street children who dare approach her American lady. “She sees me as a dollar sign,” Laurie says, and sighs. Laurie is hers, but Bindia is not Laurie’s. Bindia has made that clear, politely declining Laurie’s repeated offers of an education, of clothes, of food, of a future—if only she would come to Salvation Tree School.

For Laurie, the sight of Bindia evokes that familiar feeling of loving-sadness that’s been with her since her first visit to India in 2006. She cannot save this child, no more than she could the man with no legs, the baby thrust at her, the naked beggar boys.

“She always says, ‘No, ma’am. No, ma’am. I can’t leave here.’ Bindia’s very smart. She taught herself English. Yet people are so set in their ways, and it’s hard to change things,” Laurie says. “What you see takes such a toll on you. You see some gruesome stuff. But then I see a greener tree or a speck of blue sky. And I know something is starting to change.”

Laurie is changing, too. She is no longer tormented by the “whys” of her past. What came before was a necessary precursor for her life now.

“I struggled and wrestled with why I had the childhood I had, and if it was for this reason, then it was well worth it,” Laurie says. “God has ignited this fire within me to help these children. This is why I was born.” •

Home

Home Browse

Browse Close

Close Events

Events Maps

Maps Email

Email Brightspace

Brightspace eCampus

eCampus