Indonesia Forward

It’s a unique partnership: URI will send students and researchers to Indonesia this year, and the Southeast Asian country, which already counts URI grads among its top-ranking officials, will send government employees to Kingston. The nation of 18,000 islands, one of the world’s biggest economies, is also embarking on a dual-degree program with URI as it explores pressing issues around fisheries, marine affairs, and sustainable development, forging a path to a vibrant future—with URI helping light the way.

Words By Todd McLeish • Photos by Jessica Vandenberg ’20

When Brook Ross ’94 was growing up a stone’s throw from the Kingston campus in the 1970s, it wasn’t unusual for his family to host a group of URI students from Indonesia for holiday meals. His parents, Neil ’62, M.A. ’68 and Nancy Ross, worked for Rhode Island Sea Grant at the Bay Campus, and they collaborated with the University’s former International Center for Marine Resource Development to advise the government of Indonesia on fisheries and aquaculture development. Part of that relationship provided for Indonesian government officials to earn graduate degrees at URI, and some of those officials enjoyed annual Thanksgiving meals at the Ross residence.

dramatic, vegetation-covered limestone formations in Rammang Rammang, South Sulawesi, Indonesia.

“Because I was around these internationals all the time and hearing stories about Indonesia at the dinner table—and because we actually lived there for a year, which was mind blowing—it inspired me to pursue a career in international development,” Brook says.

He studied anthropology at URI, spent a year abroad studying and traveling in Indonesia, learned the language and culture, and even spent a month on a tiny Indonesian island where he was the only foreigner in residence. Later, while working as a banker in Rhode Island, he saw the devastation caused by the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami. He ended up returning to Indonesia to help rebuild the country’s infrastructure.

“I worked in the disaster zone for three years, and it was life changing,” he says. “I started as a volunteer with Plan International, became their relief manager helping villages with emergency supplies and rebuilding schools and health centers, and then managed partnerships for the American Red Cross doing relief recovery and retraining.”

The latter experience, plus a year working for the U.S. embassy in Indonesia, led Ross to start Indonesia Education Partnerships, a nonprofit consultancy that helps the Indonesian government establish partnerships with international universities to help move the country’s development agenda forward. The early success of his agency landed Ross on the doorstep of his alma mater.

“Every time I came home for Christmas, I looked for someone at URI who might be interested in working with me,” he relates. “Eventually I ran into Nancy Stricklin at an international education conference, and I told her we have to talk.”

Talk they did. Stricklin ’76, M.A. ’95, URI’s assistant to the provost for global strategies, was interested in Ross’s proposals, and soon introduced him to URI President David Dooley, Provost Don DeHayes, and several deans and faculty members. Those conversations have led to the establishment of a comprehensive initiative in Indonesia that includes a planned dual-degree program, faculty-led classes abroad, Indonesian government officials enrolling at URI, and numerous research projects to support the country’s sustainable fisheries, coastal management, higher-education capacity building and economic development.

Indonesia is the fourth most populous nation in the world, and has one of the world’s largest economies. Its 18,000 islands straddle the equator and span 3,000 miles.

“It’s my conviction that Indonesia is now—and will be for the foreseeable future—one of the most important countries in Southeast Asia with regard to its economy, its influence in the region, and its aspirations to become a more prominent player on the global scene,” says Dooley, who has traveled to the country three times in the last two years. “That makes Indonesia an excellent arena for engagement by URI. It’s a place where we can make a significant impact.”

Stricklin was hired to implement Dooley’s vision of expanding the University’s global presence by developing international partnerships. “URI already had partnerships abroad, but this was an opportunity to strategically explore a new region and build sustainable relationships with key Indonesian institutions,” she says.

A delegation from URI, led by Stricklin, DeHayes and John Kirby, dean of the College of the Environment and Life Sciences, traveled in 2013 to Indonesia, where Brook Ross introduced them to government officials, university leaders, and others seeking collaborations. Kirby was especially enthusiastic because much of the expertise the country needs—like fisheries, marine policy and sustainable development—could be provided by faculty in his college.

It didn’t take long for budding relationships to mature into research partnerships, study abroad opportunities, and faculty exchanges. “Very quickly we’ve become one of the most prominent partner institutions in Indonesia,” Stricklin says.

An Exchange of Ideas

While Ross was introducing URI officials to Indonesian government officials, another Indonesian official was reintroducing himself to URI.

Gellwynn Jusuf, M.S. ’90, Ph.D. ’97, until last year the secretary-general of the Indonesia Ministry of Marine Affairs and Fisheries (MMAF), earned graduate degrees in natural resource economics at URI soon after starting his career in fisheries management in the 1980s. He is one of many Indonesians who have studied at URI through the country’s Overseas Training Office program. When funding recently became available to send additional Indonesian government employees abroad to earn graduate degrees, Jusuf was in a position to encourage them to enroll at URI.

“Those who studied at URI in the 1970s went on to hold strategic positions in the Ministry of Marine Affairs and Fisheries in the 1990s. And those who studied at URI in the 1980s and 1990s can now be found to occupy numerous positions in government, research and teaching,” says Jusuf, who now serves as executive secretary of the Indonesia Ministry for National Development Planning. “I feel confident that those studying there now will lead the MMAF institution in 10 or 20 years.”

In the last four years, 21 ministry staff members have enrolled at URI to earn graduate degrees in marine affairs, environmental science and management, ocean engineering, and oceanography. More are expected to enroll in the coming years to improve their skills in managing coral reefs, fisheries, aquaculture and sustainable development.

Tono Amboro, M.S. ’18, for instance, worked as a fisheries manager in Indonesia when he enrolled in URI’s graduate program in environmental science and management in 2016. He says he hopes the degree will improve his expertise and expand his job opportunities back home. For his thesis, he is studying the life history of the tuna that live in the eastern Indian Ocean.

“I hope this research will give me a better understanding of the species so we can create a better policy for managing the tuna fishery in Indonesia,” says Amboro, who will complete his degree later this year. “URI is well known in Indonesia as a good university to learn about fisheries.”

Fery Sutyawan ’19, the assistant deputy director of fishing port management in Indonesia, decided to “start a new adventure” in 2015 by moving to Kingston to earn a doctorate in marine affairs. His research is an evaluation of the impact of several newly-authorized Indonesian fisheries policies and regulations, as well as stakeholders’ perceptions of those policies.

“I have enjoyed the URI facilities and the privileges I have to learn about U.S. marine fisheries management and other issues related to marine affairs,” he says. “But I’ve learned much more outside the campus, like the American way of thinking and culture, the advanced infrastructure and other advanced technologies, not only for scientific purposes but also for daily life.”

While the students from Indonesia are expanding their horizons in Rhode Island, many URI students from the U.S. are doing the same in Indonesia.

For the fifth year in a row, 15 students traveled to Bali in January to study Indonesian culture, biodiversity and geology in a J-term course called Balinese Temples, Komodo Dragons and Liquid Hot Magma. (A similar trip for alumni is being offered for the first time this summer.) Another class studied health care in the island nation.

“I loved that this trip helped me gain exposure to a new culture, a change in perspective, and a heightened respect for the world as a whole,” says Lesley Howard ’18, a double-major in wildlife biology and animal science. “Every single part of the trip was inspiring.”

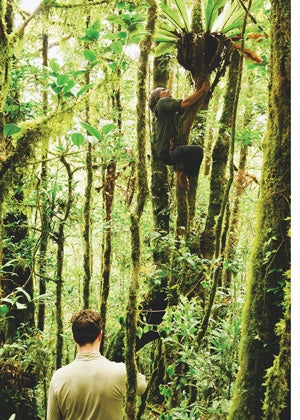

After exploring the crater of an active volcano, following rare birds through the rainforest, and waking up on a houseboat amid gorgeous tropical islands, Howard said the experience provided “a deeper meaning” than she imagined it would. “I learned that I have a love for travel, and it solidified my decision to pursue a career in wildlife research in the future.”

Clean Water, Sustainable Fishing

These exchange opportunities have provided tremendous learning experiences for URI’s American and Indonesian students, but it may be URI’s faculty who are having the greatest immediate impact.

More than a dozen faculty from the College of the Environment and Life Sciences have spent time in Indonesia in recent years, sharing their expertise in a wide variety of settings. Some have led workshops or spoken at symposiums to provide guidance and insights to Indonesian faculty and students. Others have taught scientific writing workshops or summer school classes to graduate students as part of an Indonesian plan to expose its students to scientific concepts in English.

Hydrology Professor Thomas Boving is collaborating with two Indonesian universities to promote unique technologies aimed at cleaning up local waterways and encouraging the recycling of garbage. He is advising Indonesian students on the construction of artificial “floating wetlands” that are planted with native vegetation to absorb nutrients, filter out particulates, and attract contaminants.

“The mayor of Banjarmasin wants the city to become greener, and part of his strategy is to address uncontrolled sewage using our floating wetlands in the main channel through town,” Boving explains. “He has offered us a mile-long stretch of the canal to show how it works.”

Boving is also demonstrating an inexpensive riverbank filtration system that will clean polluted drinking water in rural communities.

Assistant Professor of Fisheries Austin Humphries says food security is a serious concern in Indonesia, where delicate coral reef ecosystems provide fish and livelihood for over three million fishermen. Catches are declining as many fisheries are overexploited. So he is identifying fishery management strategies that maintain and protect the ecosystem while also ensuring that fish are available for consumption.

“A large proportion of Indonesian communities are dependent on coral reefs for food,” Humphries explains. “As these fisheries are feeling the heat from global stressors like coral bleaching, declines in fish catch are a major issue for subsistence and food security. Creating holistic evaluations of new and existing fishery management schemes is becoming more and more important to ensure sustainability over the long-term.”

A coral reef restoration project is the focus of research by Assistant Professor of Marine Affairs Amelia Moore, whose work focuses on sustainability on small island communities. She is monitoring the restoration project’s impact on an island community in Indonesia’s Spermonde Archipelago.

“The tendency is to think that small island communities are homogenous and simple, and they are anything but,” says Moore, who is working with several other researchers at URI and at Indonesia’s Hasanuddin University. “We’re trying to understand how external interventions like this can get entangled in community dynamics and relationships. Interventions are never as simple as you think they’re going to be, and they have consequences you can’t necessarily predict.”

Professor Michael Rice’s work in Indonesia started long before the recent initiative began, but it has taken on new life as a result of the recent efforts. An expert on aquaculture, he is training public officials and university extension agents in the province of Papua about the environmental effects of raising fish in cages in local lakes, reservoirs and coastal waters and how best to administer aquaculture permits.

“They know that they have a pristine fishery, and the fish they’re catching are very abundant, but they don’t want to make the same mistakes that have been made in more populated areas of the country,” Rice says. “They want us to help them set it up correctly from the beginning.”

Partners in Education

The program that launched URI’s relationship with Indonesia back in the 1970s continued off and on into the 2000s through URI’s Coastal Resources Center. Senior Coastal Resources Manager Brian Crawford, M.A. ’86, Ph.D. ’09, lived in North Sulawesi Province in 1997 and 1998, piloting new approaches to coastal resources management, establishing community-based marine protected areas, and creating a network of more than a dozen coastal universities.

“I was twice evacuated—after the rioting that led to President Suharto’s downfall and again after the Bali bombings—but we persevered through the turmoil and did some groundbreaking work,” Crawford says.

The new initiative may prove to be even more impactful, with partnerships already established at 12 universities in Indonesia. At one of them, Bogor Agricultural University, a dual-degree program is under review in which graduate students will complete half of their requirements at URI and half at Bogor.

The success of URI’s initial environmental projects in Indonesia has inspired faculty in other disciplines at the University to get involved. The deans of the colleges of Pharmacy, Nursing, Health Sciences and Engineering have traveled to Indonesia to investigate new opportunities, and two professors from the School of Education spent a week in Aceh province in 2017 developing a teacher training program designed to improve vocational education in the region.

With so many URI graduates residing in Indonesia now, many visits by University administrators have included alumni reunions that have been well attended, especially considering the size of the country and the distance many must travel. The most recent reunion was held at the home of the U.S. ambassador, who was amazed at how many people in the country had affiliations with the University.

“Our alumni have been critical in helping us develop these programs by introducing us to key players in higher education and government ministries,” says President Dooley. “They’ve been thrilled that we’re now coming to their country regularly and becoming engaged in their work.”

Dooley hopes to continue to grow the initiative by developing relationships with other government ministries and provincial governments that could send staff to URI for graduate degrees, which will likely lead to additional research and outreach opportunities for faculty and students. He is also assessing similar opportunities in other countries in Southeast Asia, perhaps in Malaysia, Vietnam or Nepal. New partnerships are being established in Ghana and Cuba as well.

“This is an exciting time for developing nations like Indonesia,” observes Ross. “By connecting them to education specialists in almost any field, they can access the best practices to fund their own development. They need URI’s expertise so they can then go home and lead these efforts themselves.”

“We’re also creating opportunities for our students to be globally engaged with cultures, peoples, viewpoints, perspectives and politics that are very different from what they might encounter in North America or Europe,” adds Dooley. “It’s a positive dynamic for everyone involved. We’re expanding horizons, growing our global footprint, and solving challenging problems all at the same time.” •

Home

Home Browse

Browse Close

Close Events

Events Maps

Maps Email

Email Brightspace

Brightspace eCampus

eCampus