A Balanced Life

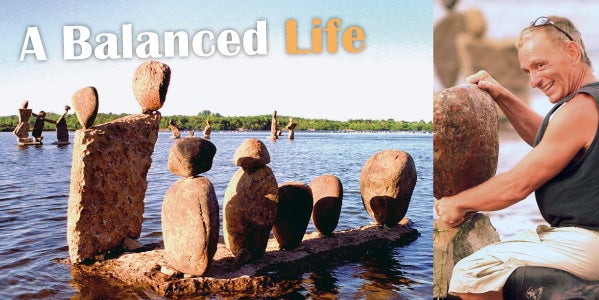

In the early summer, after the melting ice and rushing spring waters have brought the big rocks tumbling into the part of the river that passes through the Ottawa River Parkway, Ceprano begins his work. “I see a stone, and its form renders an impression in my thinking,” he says of the process. Using only the strength of his body, he hauls the rocks and puts them together, balancing the larger rocks with smaller shim rocks, to create larger-than-life abstractions that resemble human forms.

“When I install the pieces, they have to be arranged so that the rocks are equally balanced,” he says. The resulting works can be as tall as ten feet, but if no one leans on them, they’ll stand until next year’s winter ice and spring floods knock them down. “It’s a wonderful process,” Ceprano says. “I have a relationship with the entire environment: the river, the rocks, and ultimately, the public.”

How does the artist feel about the natural destruction of his work? “It’s wonderful to let nature do it,” he says. “It does it in harmony with itself. No matter how big the rocks are or how wild the current becomes, the rocks never break.”

Ceprano has been making his river sculptures since 1986 when he happened upon this stretch of river. Long a student of other cultures and religions, he discovered that certain places on earth contain a special energy—places, he says, “where there are power spots, where you can glean the energy and use it to have an empowering relationship with the earth. When I found this site, I realized I had found a place with natural energy. The place has amazing power. I really believe that.”

One day, he was in the river working on a sculpture when he heard laughter. “I turned, and no one was there. This happened several times, so finally I followed the sound and it was the water itself. Later, I was talking to an Ojibwa elder—they are very spiritual, sensitive people—and he laughed and said, ‘You heard the laughing waters.’ ”

Ceprano’s sculptures caught on very quickly with the public. “People appreciated my showing them what a beautiful place we live in,” he says. By his second year, news stories were starting to appear about the artist and his sculptures. And in 1989, he won a Canada Council Grant to continue his work.

Over the years, the river sculptures have earned the artist national renown and the installation has grown, taking on a life of its own. Now, people will often step into the river to help him with the rocks, a circumstance he welcomes since the summer of 2002 when a rock slipped and crushed his right hand, taking off a fingertip in the process. “People who come to the project are a part it,” Ceprano says. “They help make it what it is. They throw their wonderful energy into the space.”

This summer, Canada’s National Capital Commission confirmed its sponsorship of the project for the seventh consecutive year. The NCC’s sponsorship of the sculptures is in harmony with the mandate to promote Ottawa as a green city. And for the third consecutive summer, a dance group from Montreal will perform an original piece, choreographed by Claire Barret of New York City, inspired by the site.

Meanwhile, homeowners and corporations have taken note of Ceprano’s work, and he’s received a number of commissions to build private, permanent installations.

For most of us, figurative balance is a little harder to achieve, but as the free-spirited Ceprano approaches 60 this year, he’s feeling pretty good about his state of equilibrium. “The yin/yang approach has always been part of my life,” he says. “It’s not just what you balance on the outside, but inside too. Your diet, your thinking, everything has to be balanced out.”

Ceprano’s need for balance asserted itself early. He was a student at URI at the height of the Vietnam War, and the war played heavily on his conscience. “I had this sense that it was wrong for me to be so indulgent in my education when the war was going on,” he recalls. Involvement in the antiwar movement led him to Canada: “I moved to Canada not because of the draft, but because they weren’t at war.”

In 1991, he became a Canadian citizen. “The abundance of nature here is just ridiculous,” he says. “And the public health care and other social programs make the country an appealing place to live.”

He hasn’t forgotten Rhode Island, however, and he likes to get back for a visit when his schedule allows it. “I’ve thought about moving back, but I have too much work to do here,” he says. “You make your life in a place, and one day you realize this is where you made it so this is where you’re going to live it.”

When he’s not creating sculptures, Ceprano works part time as a licensed practical nurse in a rehabilitation facility for people who’ve had knee surgery or other procedures. “I like taking care of people,” he says. “The rehab is all about balance. I’m helping people to recognize their own personal balance. The two kinds of work—the sculptures and the rehab—have a kind of peculiar connection.”

He also works at his other art forms—his paintings and, in recent years, making prints from photos he takes of the rock sculptures.

Whether he’s working at his art or working to help people get back their own balance, Ceprano’s daily goal is to contribute something to the world. “Every day,” he says, “is an opportunity to produce something, to contribute something.”

To see more of this artist’s remarkable work, visit his Web site at jfceprano.com.

By Paula M. Bodah ’78

Photos By John Felice Ceprano

Home

Home Browse

Browse Close

Close Events

Events Maps

Maps Email

Email Brightspace

Brightspace eCampus

eCampus