Going Viral

The mystery Rothman is trying to crack involves dengue fever, and the National Institutes of Health (NIH) is betting heavily on his research, to the tune of more than $21 million in two separate grants of $10 million and $11.4 million awarded in 2013 alone—an all-time high for URI research.

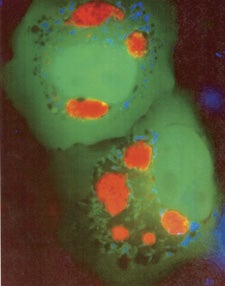

Dengue fever, a mosquito-borne viral hemorrhagic disease, is a cousin to West Nile Virus and is found largely in Thailand, the Philippines, Vietnam, Central and South America, and the Caribbean. Cases have been reported in Florida and the Gulf Coast of the United States, and there was famously an outbreak as far north as Philadelphia. Rothman likens dengue, also known as breakbone fever, to a horrible flu—“You feel absolutely miserable, like you are going to die, but you don’t.” Rothman’s research focuses on virological and immunological events in acute dengue infection and their relationship to the development of viral hemorrhagic fever syndrome.

So how did a promising young medical student from Brooklyn, N.Y., become a lead researcher in the quest to find a vaccine for dengue? And how did he land at iCubed (the Institute for Immunology and Informatics) at URI?

I’Cubed

Immunology & Informatics

To improve human and animal health by applying the power of immunomics to the design of better vaccines, diagnostics, and therapeutics.

immunome.org

Infectious diseases (ID) was an area Rothman studied first during his training at the Medical College of Virginia, where he did his residency after graduating from Boston University Medical School. An ID fellowship at the University of Massachusetts Medical School in Worcester followed. Joining one of the only labs in the country at that time working on the immune system’s response to dengue, Rothman was hooked.

“ID is the most interesting area of medicine,” Rothman states emphatically. “New infectious diseases are developing all the time. The human body stays the same, but microbes continue to evolve and develop resistance to antiretroviral drugs.” When he started his research in 1987, Rothman notes, only a handful of labs were studying the immunology of dengue; now, dozens of labs are immersed in this work.

Part of the reason for this burgeoning interest, Rothman says, was the post-9/11 anthrax scare. The emergence of HIV in the 1980s also provided tremendous impetus for the study of immunology and virology.

Rothman made the leap from Worcester to Providence in 2011. Annie De Groot (a co-founder of iCubed) and Rothman were both program directors for similar grants within NIH’s Collaborating Centers of Human Immunology program. So once he decided to make a change, “It made sense to reach out to Annie.”

Part of the appeal of iCubed for Rothman is its collaborative nature; on the $11.4 million grant, URI is working with Lifespan’s Center for International Health Research. Other partners are University of Massachusetts Medical School, University at Buffalo and Upstate Medical University, the United States Army’s Walter Reed Army Institute of Research, the Armed Forces Research Institute of Medical Sciences in Bangkok, and a Massachusetts-based biotechnology company. Rothman is also pleased that the grant involves mentoring junior researchers in the field.

The professor hopes his work on dengue will inform research on other viral hemorrhagic fevers and possibly the development of a vaccine or other treatment. He emphasizes that he sees himself as an immunologist who facilitates vaccine development rather than as a vaccine developer per se.

“Dengue is perfectly evolved for infiltrating the population,” notes Rothman. “The sobering reality is that cases are increasing every year and we are losing the battle against dengue. There are hundreds of millions of new infections per year and it’s estimated around 20,000 deaths. But the good news is that we have a much better ability to detect and diagnose the disease, and promising technologies are available to an increasing number of labs.”

Additional progress, according to Rothman, includes the development of a simple liver function test that can predict the likelihood of severe dengue.

Rothman says the greatest challenge is in simplifying the immunological system’s response to dengue as much as possible in order to study it. “It is a complex pathogen,” he says. “I have come to respect the thing we are fighting against.”

Rothman continues to make his home in Framingham, Mass. His wife, Lori Bornstein, an electrical engineer, has had a successful career in computer chip design. Their older son, Marc, is a freshman at Harvard; their younger son, Eric, is in 10th grade. Not surprisingly, the boys are strong math and science students, but Rothman stresses that there is no pressure on them to follow in their parents’ footsteps.

And what does this medical sleuth do to relax? Rothman laughs at the question, claiming his work is so engaging he doesn’t find the need to unwind. He does, however, enjoy crossword puzzles, Sudoku, and KenKen—the kind of puzzles that in his words, “inevitably proceed toward a solution.” On the other hand, he concludes, “Science doesn’t have an answer key.”

— Melanie Coon

Home

Home Browse

Browse Close

Close Events

Events Maps

Maps Email

Email Brightspace

Brightspace eCampus

eCampus