Learning What Fish Know

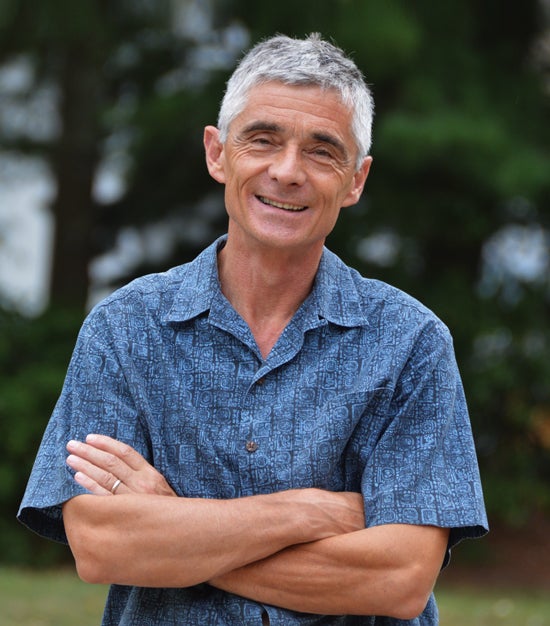

There’s something fishy about electrical engineering Professor Godi Fischer’s research. His work in establishing an underwater positioning system depends on fish going about their daily lives.

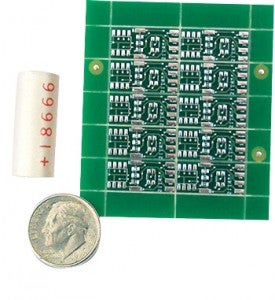

Backed by the National Science Foundation, Fischer is using dime-sized hydrophones that serve as housing for all the electronic components of a miniature acoustic receiver. The 1-inch-long tubes are destined for the dorsal fins of unsuspecting fish. By listening for a specific sound frequency emitted by underwater speakers, the receivers will triangulate the fish’s exact position. The position, along with data like water temperature and depth, is stored on non-volatile memory.

The low-cost, minimal-infrastructure system opens the door to tracking fish migrations, fish stocks and ocean currents. The information could help policymakers set appropriate fishing quotas, and climate-change researchers understand how the ocean shunts heat around the globe.

“There’s a lot you can track,” Fischer says. “The issue was how to make these things very small and very low power.”

Fischer leaned on his years of expertise in circuit design to shrink the sensors and related electronics on to a circuit board just 8 mm by 17 mm. The equivalent of two souped-up watch batteries provide power for up to two years.

Fischer got the idea a few years ago after bumping into fisheries expert Conrad Recksiek, now a professor emeritus, who noted that we know surprisingly little about fish migrations. Researchers cannot use traditional GPS because water absorbs those signals. To solve the problem would require a multidisciplinary approach.

To round out the team, the pair approached oceanographer Thomas Rossby, also now faculty emeritus, who was using a similar, but significantly larger, system he calls RAFOS floats. It took a few years, but eventually they came up with a design based on a novel custom microchip.

“That’s why it’s fun to work together across disciplines,” Fischer says. “It exposes you to different applications you wouldn’t see working independently.”

The trio hopes to deploy the first prototypes on real fish by summer 2015. They aim to tag fish in Narragansett Bay in Rhode Island, or off George’s Bank to the northeast of Cape Cod. To incentivize fishermen to return the hydrophone-carrying fish caught in their nets, researchers will likely launch a contest. Each hydrophone carries a unique serial number and the person who returns one lucky number will win a prize.

For those worried about the fish themselves, Fischer says most probably won’t realize they are transporting pioneering research equipment.

“We have an interest in the fish being OK,” Fischer points out. “If they don’t survive, our equipment is useless.”

—Chris Barrett ’08 MPA ’14

Home

Home Browse

Browse Close

Close Events

Events Maps

Maps Email

Email Brightspace

Brightspace eCampus

eCampus