Fossil identified as from extinct megalodon

Dec. 7, 2022

From floor to ceiling, the University of Rhode Island’s Marine Geological Samples Laboratory is jammed with tons of sediment cores, volcanic rocks and other marine samples. Daily, lab workers sort through marine materials recently delivered by research cruises, cataloging the samples for loan to researchers, educators and museums.

“You see these rocks in your sleep,” said Danielle Cares, assistant curator of the repository. “They’re interesting, but mostly to scientists.”

That changed one day about a month ago. Cares and two graduate students—Molly Robinson and Jason Almeida—were going through a shipment from the research vessel Nautilus—about 20 boxes, each weighing around 50 pounds, of ferromanganese-encrusted rocks from about 10,000 feet deep in the Pacific Ocean.

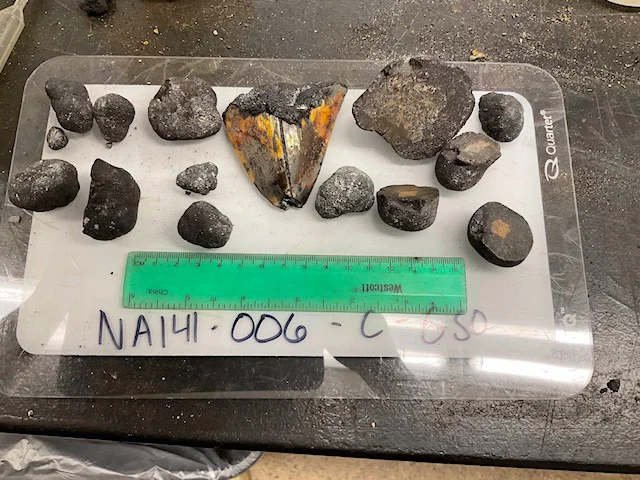

Hiding, covered in the black crust, was a fossil of a shark tooth—which has since been identified as belonging to an ancient megalodon, a species of shark that became extinct around 2.6 million years ago. Mentioned on Facebook by the Ocean Exploration Trust (Nautilus Live), news of the find has appeared in numerous media outlets, including Newsweek.

“It was so exciting,” said Robinson of finding the tooth. “We get a lot of cool rocks here, but we don’t get fossils.”

That morning, as Cares entered descriptions of the samples into the laboratory’s database at URI’s Narragansett Bay Campus, Robinson was photographing a ferromanganese nodule when she noticed small ridges protruding from the crust. The ridges didn’t look like anything she might have made with the rock saw, and she asked if she should chip off the rest of the crust. Immediately, they recognized they had uncovered a massive tooth, about the size of a person’s palm.

“We were giddy like it was Christmas for a week,” said Cares. “There were a couple of people in different labs down the hall and we got them in here. We were all like, ‘Oh my God, this is the best thing ever.’”

Identifying the tooth

Cares said they didn’t initially think the fossil was from a megalodon. But she contacted David Ebert, a modern shark researcher at San José State University and program director of the Pacific Shark Research Center, who preliminary identified the tooth as belonging to the long-extinct predator.

“The morphology of the tooth looks clearly to be [from] a megalodon,” he said in an email interview. “To further confirm the species, I would recommend asking a paleontologist familiar with this group.” (A paleontologist has since agreed with Ebert’s identification.)

According to the Encyclopedia Britannica, megalodons were among the largest fish to ever cruise the oceans, about three times bigger than the largest sharks today. Their name means “giant tooth” in Greek, and their teeth were about three times longer than the average tooth of a modern great white.

It’s difficult to determine when the massive sharks went extinct because the fossil record is incomplete, but the youngest fossils are about 2.6 million years old, according to the website Live Science. Fossil remains have been found off the coast of every continent except Antarctica, according to the Encyclopedia Britannica.

Ebert said that finding a megalodon tooth fossil is not that unusual depending where you are, but it might be a record for the location where Nautilus uncovered the fossil.

The fossil was discovered over the summer during an Ocean Exploration Trust expedition to Johnston Atoll. The tooth was among samples collected by a remotely operated vehicle from the ocean floor, about 3,000 meters down, within the Pacific Remote Islands Marine National Monument, an unincorporated U.S. territory.

“I think this is a new record for this part of the Pacific Ocean,” Ebert said. “I do not know the range of these sharks, but I think they were global in their distribution as their teeth have been found on most all continents.”

Oceanography Professors Katherine Kelley and Rebecca Robinson, co-directors of the Marine Geological Samples Lab, have been overseeing identification of the fossil with the help of Ebert, who contacted shark paleontologists for their expertise.

“Through them, I think we’ll be able to get a more detailed identification of the species and possibly an age range,” Kelley said.

Cares, Robinson and Almeida might have provided an estimate at the fossil’s age. When they uncovered the tooth, just over a millimeter of ferromanganese crust was around and inside the tooth. “For ferromanganese crust, it takes a long time to build up,” Robinson said. “For a rough estimate, it takes a million years to build up a millimeter of this crust.”

Mission of the samples lab

Kelley likens the Marine Geological Samples Lab to a lending library of sediment core and rock samples from the ocean floor. The 6,800-square-foot facility, which stores and preserves samples—including sediment cores, volcanic rocks, seafloor glass, and hydrothermal vent samples—is one of four National Science Foundation-funded repositories in the country. The samples are photographed and described in a database, enabling researchers, educators and museums to request them.

“These kinds of materials are really difficult and expensive to collect when scientists go out to sea,” said Kelley. “Our job is to make sure the investment that was made in collection of these samples is returned many times over through the archival of materials for continued scientific research.”

For Robinson and Almeida, the repository is providing samples to their own research now, and their work is giving them a knowledge of the repository that will help them going forward.

Robinson, a second-year Ph.D. student who works on paleoclimatology in Rebecca Robinson’s lab, uses microscopic fossils found in the sediment samples to study climate conditions millions of years ago. Almeida, a second-year master’s student, studies submarine volcanoes in Oceanography Professor Adam Soule’s lab and uses the volcanic glass samples in his research.

“Working here has been great,” he said. “We get to see how to do rock descriptions and what happens to samples. So, when you’re out on a research cruise, you know where the samples end up and how they’re stored. It’s good knowing there are repositories where, if you need something in your research, you can check the databases and see if anything useful has been collected.”

The lab’s collection now will include an ancient shark tooth, which, like the sediment cores and rocks, may be loaned out for future research.

“If the scientific community is as interested as the general public in the tooth, I imagine it will spend a lot of time in circulation going to different laboratories for study,” Kelley said.