By Holly Morin

The Arctic is considered a region of extremes with acute shifts in seasonal daylight, intense cold, and high winds. As average air temperatures in this polar region are rising more rapidly than other parts of the world, it is now also a region of extreme climatic warming. The changes happening on land and in the sea will not only affect the people and animals that live in the Arctic but will impact the entire globe.

Understanding and documenting the changing Arctic is critical. However, the difficulty and expense of conducting polar research makes it challenging to study the region’s rapid transformation. A multidisciplinary group of scientists, students, social scientists, and filmmakers set sail on the Swedish Icebreaker Oden to investigate and communicate how waters and fauna of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago have changed as a consequence of rapid climate warming.

ABOUT THE PROJECT: From July 18 to August 4, 2019, with major funding provided by the National Science Foundation and additional support from the Heising-Simons Foundation, a University of Rhode Island Graduate School of Oceanography team led an expedition to study the Arctic’s Northwest Passage as part of the Northwest Passage Project—a collaborative effort between GSO’s Inner Space Center, the film company David Clark Inc., the Swedish Polar Research Secretariat, three informal science education institutions, and five U.S Minority Serving Institutions.

Investigating a Changing Arctic

Since 1979, the summer extent of Arctic sea ice has decreased by 30%, but the total summer volume of sea ice has decreased by more than 66%. Changes in sea ice influence freshwater movement in the Arctic, which could affect the Earth’s “ocean conveyor belt,” the constantly moving, density-driven system of deep-ocean circulation that transports heat and sequesters greenhouse gases around the globe. Decreasing sea ice also reduces surface albedo (reflectivity of the sun’s energy) in the Arctic. Lower albedo means more of the sun’s energy is absorbed at higher latitudes, amplifying the effects of polar warming. Continued Arctic warming influences the polar jet stream and wind patterns, affecting other regions outside the Arctic. In addition, less thick and abundant sea ice means reduced critical habitat for animals, such as Arctic fox, polar bears, and walruses, as well as potential changes in the timing and abundance of phytoplankton blooms, the foundation of the marine food web.

The comprehensive science plan for the Northwest Passage Project (NPP) sought to investigate some of these conditions and fill important data gaps for the Arctic region. NPP science activities, led by chief scientist and GSO professor, Brice Loose, were centered around four major research themes: water mass properties and circulation; water column chemistry and greenhouse gas flux; microscopic communities in transition; and distributions of Arctic seabirds and marine mammals. Nineteen onboard undergraduate students actively worked alongside ocean and atmospheric scientists to collect water, ice, and air samples during the expedition’s 2,000 nautical mile route through the Northwest Passage. Although each student focused on one of the four research themes, they all participated in the full scope of NPP activities to give them insight into the multidisciplinary nature of ocean science.

“NPP’s greatest strength is connecting different concepts to understand climate change as a phenomenon through different lenses,” said Humair Raziuddin, an undergraduate at the University of Illinois at Chicago. “And this idea of combining different perspectives and concepts to understand a topic is something I will never forget.”

Students gained skills in preparing, launching, and gathering samples from the conductivity, temperature and depth (CTD) rosette, the oceanographic workhorse of the cruise. A total of 53 CTD casts were completed during the expedition. Student teams collected and logged hundreds of water samples from the CTD rosette to investigate levels of carbon, methane, nutrients, and chlorophyll and used additional samples in onboard plankton experiments. The students also collected 124 seawater surface samples, providing data critical to understanding the water cycle and ocean/atmosphere gas exchange. NPP students and scientists conducted marine mammal surveys and documented 22 different seabird species in addition to numerous marine mammals including polar bears, walrus, bearded seals, and bowhead whales. Loose also led student teams onto the ice floes to collect ice cores to measure characteristics such as temperature, salinity, methane and carbon dioxide concentrations, and plankton abundance, as well as to determine the presence of microplastics.

NPP undergraduate and graduate students were motivated and enthusiastic expedition participants who put in long days during the course of this immer-sive research experience.

“One of the greatest rewards of the cruise was watching the progress of the undergraduates,” said GSO graduate student and the NPP microscopic life science lead, Jacob Strock. “While many began the trip with little oceanographic experience, by the end of the cruise they had mastered important lab skills, were asking meaningful scientific questions, and were even teaching each other. I think many are now ready for the next steps in their scientific education and careers.”

Communicating About a Changing Arctic

For many, the Arctic may seem remote in terms of both geography and relevance. So connecting broad audiences to the changing Arctic, as well as NPP science activities, was an important project goal. Knowledge exchange, including that with local, indigenous communities, is vitally important to understand and plan for the future of the Arctic, and to provide a foundation for informed decision making.

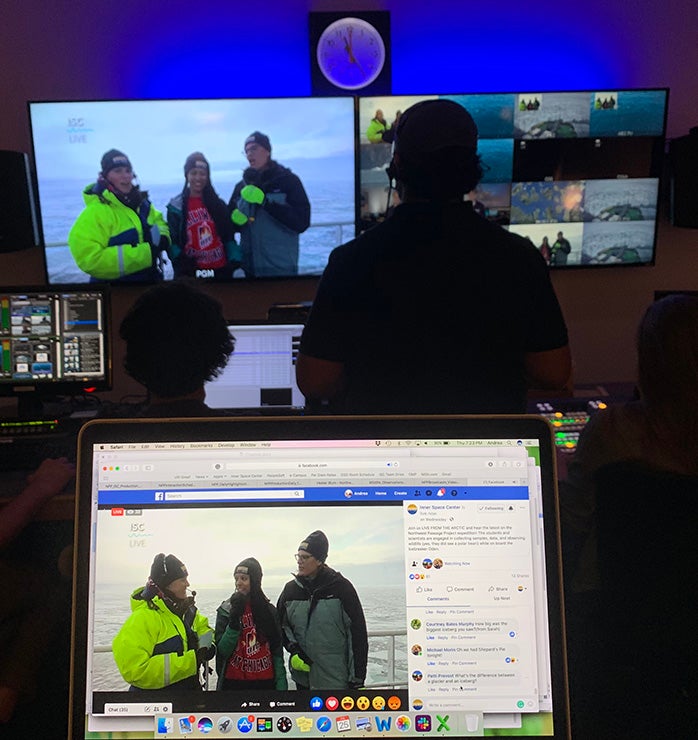

Similar to the NPP science plan, the expedition’s communication plan was comprehensive, and provided unprecedented opportunities for broad audiences to follow and interact with the NPP expedition in real time. The expedition delivered the first-ever live, interactive broadcasts from a ship in the Northwest Passage to the Smithsonian Institution National Museum of Natural History, San Francisco’s Exploratorium, and the Alaska SeaLife Center. To reach a broader public audience, three Facebook Live events also took place from the Oden. Using the Inner Space Center’s advanced telepresence technologies and video production facility, NPP completed 40 live, informative and visually-stunning interactive broadcasts during the 18-day expedition. NPP student participants co-hosted each live broadcast with the ISC’s onboard host, Holly Morin, and NPP scientists provided commentary and answered audience questions.

Some audiences were even treated to a rescue of a passive acoustic recorder that had broken free and was drifting in the ice in Lancaster Sound. The rescue provided an opportunity for the hosts to explain the importance of the instrument, which had over a year of underwater recordings of whale vocalizations, ships, and other Arctic sounds. The rescue also offered a chance to discuss the value of international collaboration and field support for polar research.

In addition to the many live interactions, NPP activities and the experiences of the diverse group of expedition participants were captured by the onboard film team of Emmy Award-winning documentarian David Clark. The 90-minute, ultra high-definition documentary, Frozen Obsession, will offer audiences a deeper look at the experience of Arctic exploration. The film will also explore the maritime history of the Northwest Passage, indigenous Arctic history, how modern changes are affecting the traditional way of life, and the changing geopolitics of an ice-free Arctic.

Experiencing a Changing Arctic

NPP participants also had opportunities to leave the Oden and visit several locations within the Northwest Passage. These included visits to Pond Inlet, a Nunavut community tucked into the mountains and glaciers of Bylot Island and Baffin Island. The group shared a meal with local indigenous community members and toured the village with members of Ikaarvik, a local research group that works to bridge modern polar science with traditional knowledge. The NPP team also had the opportunity to visit Beechy Island, a historic site in the Northwest Passage that marks the final resting site for several members of the Franklin expedition. The beauty of the pristine Arctic environment, the shades of blue and orange, and the sun that never set, made a distinct impression on many NPP participants.

The Impact of NPP

Although some preliminary results have been reported, data from the NPP expedition is still being analyzed. It is clear, however, that the NPP experience has made a lasting impact on its participants.

“The thing that set the Northwest Passage Project apart was the sense of purpose that united this diverse crew of participants—ages from 19 to 75, and cultures from Swedish to Pakistani to Inuit to Californian,” said Loose. “The wonder of the Arctic and the shock of the record warming in summer 2019 sharpened our focus on the activities of science and communication as a means to comprehend the change that was unfolding around us.”

This sense of purpose and discovery has bolstered scientific motivations for many NPP student partic-ipants. “After this trip, I am more sure of my ability to form meaningful connections in science,” said Virginia Commonwealth University undergraduate, Mirella Shaban. “I have found a part of myself that I know fits in the world of science and research.”

Perhaps this was most evident for one of the two Inuit participants on the expedition, Mia Otokiak. “Being an Inuit youth, you know there are statistically less opportunities for you, especially in the scientific world.” Mia said. “This expedition has showed me that I can do research, I can take part in important decisions, and I can be a scientist. And even though before I went on the sail I had always known I was a researcher/scientist, this sail gave me more confidence in being one.”

The multi-disciplinary NPP was conceived by GSO’s principal investigator Gail Scowcroft, and co-principal investigators Dwight Coleman and Brice Loose, in partnership with co-principal investigator David Clark. The project and its expedition took several years to plan, and the National Science Foundation provided all the logistical support for the expedition. Scowcroft, associate director of the ISC, is delighted that GSO could make such an important contribution to science as well as the education of the participating students and public.

“The rapidly changing Arctic environment is an issue of global importance. Challenges to educating the public and communicating the realities and impacts of the changing Arctic must be overcome with credible, understandable science and proven methods of climate education,” Scowcroft said. “The NPP is meeting these challenges, and we are extremely grateful to the NSF for giving us this opportunity. We are blessed with a top shelf team for this project, and it would not be

as successful without the leadership of chief scientist, Brice Loose, and ISC director Dwight Coleman, an international leader in telepresence technology, who directed the shore-side operations of the expedition. We are now looking forward to the analysis of the data and the release of Frozen Obsession.”