Once Upon A Shop Floor

The little-known story of the man whose eureka moment—along with his remarkable tenacity and political savvy—changed your life (and that of all your classmates)

The little-known story of the man whose eureka moment—along with his remarkable tenacity and political savvy—changed your life (and that of all your classmates)

By Jim Leslie

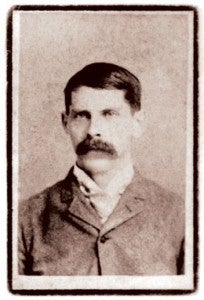

What is now the University of Rhode Island was founded by a Kingston shopkeeper and part-time postmaster who overcame tremendous odds and political opposition to realize his dream. His name was Bernon Elijah Helme. Nowhere on the campus is there a single plaque or structure to carry his name, and few alumni are familiar with his efforts. He is a forgotten man.

In 1888, Helme (his name is also spelled Helm in some histories) raised $2,000 from 30 people to purchase the 140-acre Oliver Watson Farm in Kingston as the location for the state’s Agricultural School and Experiment Station.

In the late 19th century, $2,000 was a significant sum of money. For example, the college’s first president received an annual salary of $1,600. Yet Helme also persuaded the Town of South Kingstown to contribute the same sum (awarded on a split vote).

The farm was eventually given to the state, which needed to come up with just $1,000 to meet the selling price of the property. This was the nucleus for what was to become URI, but there was a long road ahead filled with rancorous and prolonged political debates.

Let me set the scene a little: In 1888, Kingston was a thriving farm center with a post office, church, bank, tavern, grade school, courthouse, jail, a blacksmith’s shop, and a private finishing school—which attracted young ladies from as far away as Cuba, according to one report.

South Kingstown in general was also thriving. The wealthiest agricultural town in the state, it boasted more than 100 farms within its boundaries. In 1890, the U.S. Census listed 6,231 inhabitants in South Kingstown, compared to 8,099 in Cranston, for example.

Helme, an 1877 graduate of the Friends School in Providence (now Moses Brown), was a prominent citizen in Kingston: clerk of the church, a trustee of the Kingston Savings Bank, and a leader in the temperance movement, as well as part-time postmaster and small business owner. Art lovers may recall that the South County Art Association, just off campus in what remains of the Kingston village center, is housed in a building that still bears his name: Helme House. According to the Reverend J. Hagardon Wells, then pastor of the Kingston Congregational Church, Helme came up with the idea of establishing a college in Kingston while sweeping the floor in his store.

Wells wrote: “But there is one important and indubitable fact in regard to the location of the R.I. College of Agriculture and Mechanic Arts in Kingston, which I am morally certain will be buried in deep oblivion unless I embalm it in imperishable history. I happened sometime in the last of the 80s to be in the store along with Mr. Helme. He was sweeping the floor… and exclaimed: ‘Mr. Wells, Mr. Wells, I have got an idea. I’ll tell you but don’t say anything yet.’”

The idea was for an agricultural school to be located on the Watson farm, near the village, fully paid for, with an agricultural experiment station attached.

Helme and his allies saw the Hatch Act of 1887 as a way to go forward. It gave federal funds, initially $5,000, to state land-grant colleges in order to create a series of agricultural experiment stations, as well as to provide agricultural information, especially in the areas of soil minerals and plant growth. The problem at this point, however, was that Brown University had already been named Rhode Island’s land-grant school in 1863, in accordance with the first land grant act, also known as the Morrill Act, named for the U.S. Senator Justin S. Morrill from Vermont.

The purpose of land-grant colleges was to teach courses related to agriculture and the mechanic arts (engineering) as prescribed by the legislatures in each state “in order to promote the liberal and practical education of the industrial classes…” They were also required to teach courses in military tactics, so ROTC programs were created.

Farmers in the state, who complained that Brown’s curriculum was not preparing students to become farmers, mounted a campaign to cut Brown off from Hatch funds. Instead, they lobbied for an agricultural school and experiment station that would meet their needs, so in 1888 the Rhode Island State Agricultural School was created by an act of the General Assembly. The first students arrived in Kingston in September 1890, after the erection of three buildings, including College Hall (later renamed Davis Hall). The four floors of this building housed classrooms, administrative offices, and other facilities.

College Hall and the experiment station were built with stone quarried at the foot of Kingston Hill and hauled up on tracks to the building sites by oxen. The quarry, just east of today’s football field, is now flooded. Some stone was also taken from what is now the quadrangle.

The next battle arose with the passage of the second land-grant act. Again, the issue was whether Brown or the newly established agricultural school at Kingston should get the funds. In May 1892, the legislature again decided to give the funds to the Kingston school, but in the process they also rechartered it as the Rhode Island College of Agriculture and Mechanic Arts. This is the official birth date for the college that would later be rechristened Rhode Island State College and eventually the University of Rhode Island.

When the news of this turn of events reached Kingston, there was wild rejoicing. The afternoon that Helme returned from Providence, where he had spent the week lobbying, he was met at the railroad station by a group of students who had borrowed a carriage, without a horse, to pull him up the hill. Residents and coeds strewed flowers and ferns in the path of the carriage, as it moved up to his home.

As darkness cloaked the village that night, there was the thunderous roar of a cannon, called “Old Ben Butler,” which students had borrowed to celebrate. Their celebration continued throughout the night. At dawn the students were tired, but decided on one last mighty blast. They stuffed the cannon with all the remaining powder and lit it. When the smoke drifted away, they found that the cannon barrel had ruptured. Today that cannon rests on the southwest corner of the quadrangle, across from the Carlotti building.

After 88 eventful and productive years, Helme passed away. He lies buried in a tiny cemetery at the corner of Torrey Road and Route 1 in Wakefield. He had no offspring or wealth, but the “college” was his legacy. As you know, it has grown and prospered. •

Note: Much of the information about Helme comes from a diary kept by his brother and available at the South County History Center. The University of Rhode Island: A History of Land Grant Education in Rhode Island by Herman F. Eschenbacher is also a reference.

Photos: URI Special Collections

Home

Home Browse

Browse Close

Close Events

Events Maps

Maps Email

Email Brightspace

Brightspace eCampus

eCampus