Starting Over

After a terrifying flight from danger and oppression, some 200 political refugees settle in Rhode Island each year, only to face the exhausting task of starting from scratch in an unfamiliar culture. Omar Bah ’10 gives them the space, and courage, to restart their dreams.

By Elizabeth Rau

Monday morning, on a rainy day in Providence, Omar Bah is making his rounds. First, he visits Florence Gaye, a native of Liberia, to check up on her and gab about Christmas. Santa, he says, will drop by later in the week with presents. Then he drives a couple of blocks to see Burundi-born Revokata Nzinahora. Part cheerleader, part father figure, he gently nudges her about a career.

“You’re doing a great job,’’ says Bah, hugging her toddler, still in pink pajamas.

“I really want to be a nurse,’’ says Nzinahora.

“You will,’’ Bah says.

Nothing is impossible for Bah and the hundreds of refugees he’s helped as founder and director of the Refugee Dream Center in Providence—quickly becoming the go-to place for recent arrivals seeking guidance, or just someone to talk to. Bah is the perfect listener. Their story is his. “I’ve passed through the same journey,’’ he says. Not only does he know what they’ve experienced—political oppression, for one—he knows what they can do, given support and resources. He happily puts himself out there as a role model, a shining example of what can be accomplished with persistence, hard work and a heavy dose of compassion.

A mere decade ago, he was left for dead, curled up in a mosquito-infested prison cell in Gambia, lying in a pool of his own blood. The butt of the soldier’s AK-47 had come down hard, crushing his skull. The bayonet had sliced his back. He thought he was dying. It all seemed so unreal—beaten and jailed for writing newspaper stories criticizing the West African country’s brutal dictator. Just when he thought it was over, the door opened, giving him a second chance at life—and reporting the truth. He was relentless because “Good governments don’t beat you.’’ For the next few years, he continued to expose murders, torture and anti-gay killings, making a name for himself as a journalist in one of the most repressive countries in the world. Then the henchmen came again. This time, he had no choice. He had to flee.

Today, he’s a U.S. citizen, a graduate of the University of Rhode Island, a man with a country. Considering what he’s been through, he could’ve been content to live out a picket-fence life in his adopted state. But, at only 36, he’s doing so much more. Besides leading the refugee center, he lectures throughout the country about the challenges refugees and immigrants face. He’s met with Rhode Island Senators Jack Reed and Sheldon Whitehouse and represents Rhode Island and the Northeast at the United Nations High Commission for Refugees. A Muslim, he is also defending his faith against the backlash from events in San Bernardino and Paris. And he still finds time to write, most recently a memoir, Africa’s Hell on Earth: The Ordeal of an African Journalist.

Growing up in a small village of 800 without electricity or running water, Bah knew early on that he didn’t want to herd cattle like the other men in his tribe. He studied law in Serrekunda, Gambia’s largest city, then switched to journalism after shadowing lawyers in the courts and realizing that cases about political corruption were not making their way into the newspapers. Being a reporter, he figured, would be the best way to make public the cruelty of Gambia’s dictator, Yahya Jammeh. When government censors cracked down, despite the punishment he’d taken, Bah secretly fed reports to an American-based website called the Freedom Newspaper.

Different Countries, Same Story

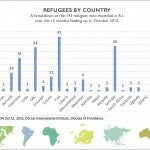

About 200 refugees from countries as different as Nepal and Rwanda arrive in Rhode Island every year to start a new life. And their journey is usually sparked by the same thing: war.

Ten years ago, Liberians fleeing a bloody civil war topped the list, followed by refugees from Burundi, Eritrea and Rwanda, says Baha Sadr, refugee resettlement services director for the Dorcas International Institute. Today, the highest numbers are from Iraq, the Congo and Somalia—all countries terrorized by decades of war.

The next group to arrive: Syrians. Sadr says Rhode Island has a thriving Syrian community that would be happy to support and guide Syrian refugees as they find their way.

“Refugees are especially driven,’’ says Sadr. “They’re like Omar. When they come here they want to be useful and give back to their community. Helping refugees resettle is a huge investment we make in humanity. We’re all in this together.’’

But in 2006 the government hacked the site, revealing Bah as the top writer. A friend tipped him off with the frantic phone call that started his flight: “They are coming for you. Run.’’ His knees buckled.

Hours later he boarded a bus to nearby Senegal, leaving behind his wife of two months, Teddi Jallow. He almost didn’t make it. At the border, a soldier pointed a gun to his head. “I raised my hands to surrender,’’ says Bah. Then, the unexpected. The soldier was a friend from childhood. Their eyes locked in horror, and the soldier let him go—a “bold and brave’’ decision, says Bah. “He could’ve been killed for sparing me.’’

In hiding in Senegal, Bah watched television reports of Gambian soldiers declaring him a wanted man. The stress took its toll. The sickly man in the mirror with bulging red eyes and hollow cheeks looked near death. Word got out that Gambian thugs in Senegal were hunting him down, so he fled to Ghana, where he lived for nearly a year with the Media Foundation for West Africa looking after him as it lobbied to get him to the United States.

His plane landed at T.F. Green on May 24, 2007. The Dorcas International Institute scooped him up and guided him over the next few months with everything from finding an apartment to grocery shopping. Home was a three-bedroom apartment on Federal Hill in Providence with refugees from Liberia and Burundi. Bah was alive, but lost. The loneliness hurt. He missed his wife, his mother, his friends. He had no idea how to use a gas stove or turn on the shower. Why do people walk so fast? How does the bus pass go in the slot?

But he had two things that set him apart: his mastery of English and his spirit. Within a few months, he landed a job as an escrow representative at Rhode Island Housing, and started taking evening classes at URI’s Providence Feinstein Campus—a “wonderful learning’’ institution. In 2010, he graduated with a degree in communication studies and went on to get his master’s in public administration from Roger Williams University in Bristol, R.I.

But refugees were always on his mind. Over the years, he had helped new arrivals from throughout the world—Iraq, Myanmar, Rwanda, the Congo and Somalia, among others—find cleaner apartments, fill out job applications, apply to schools. What he discovered is that most refugees need years of guidance, beyond the initial first months. “It’s a total shock,’’ says Bah. “They’re free and safe, but it’s so difficult to come to a new country and start over. I see myself as an expert through my own experience.’’

The Refugee Dream Center, founded last year and funded, in part, by the Rhode Island Foundation, educates refugees about health care and job opportunities, offers English language classes for adults, organizes after-school and mentoring programs for children and even makes house calls. Trauma counseling is available—a must for many who have been tortured, even raped. “I want to be an example for other refugees,’’ says Bah. “Despite all the challenges, opportunities are here. Refugees can do it.’’

Face-to-face visits are one of the most important parts of his job, he says. Gaye, living in Providence for a decade after fleeing civil war in Liberia, celebrated Thanksgiving at the center with Bah, along with 70 other refugees, including Jallow, who came over in 2009, and the couple’s American-born sons, Barry, 5, and Samba, 3. Nzinahora went to the dinner too. She’s grateful for Bah’s support. She lived in a refugee camp in Tanzania for a decade before coming to Providence. “He’s like a brother to me,’’ says Nzinahora. “Thank you,’’ says Bah. “No problem,’’ she says. Their next collaboration: a clothing drive for children in Burundi, one of the poorest and most dangerous countries on the planet. Bah’s eyes light up. He says, “We can do it.’’ He’s come so far. A half-moon scar from the bayonet wound still marks his back, but he is looking ahead. •

Home

Home Browse

Browse Close

Close Events

Events Maps

Maps Email

Email Brightspace

Brightspace eCampus

eCampus