A Life in Words

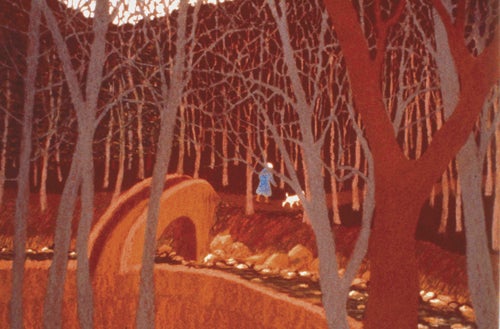

- “Not Seeing is Believing” by Sylvia Petrie is featured on the front cover of The Collected Poems

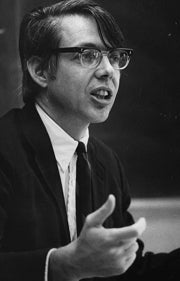

Poet and URI professor Paul Petrie was a writer of boundless energy.

By Elizabeth Rau

Paul Petrie died listening to his poems. At the hospice in Providence, his wife, Sylvia, and their children took turns reading aloud at his bedside. Groggy from morphine to numb the cancer, the poet and former University of Rhode Island professor could still hear the song of his verse.

Always the hilltops take me,

and always I go—

over the slight green rise at the end of fields,

over ridges of blue

distance—and on—where to—none know.

The end came on Nov. 9, 2012, at the age of 84 and a short two months after he had been diagnosed. Sylvia wondered how she would go on, her world so entwined with Paul’s they had moved as one through 58 years of marriage.

The book, she says, saved her. She spent a year helping to edit his poems, which he had arranged just as he wished them published before he knew he was dying. The fruit of her devotion is The Collected Poems, a vast and beautiful 754-page love letter to life.

Pulitzer Prize-winning poet Philip Levine called the poems astonishing, and Paul a writer of boundless energy: “Considering how little attention the poetry reading public—if there is such a thing—gave his work, his 70-year commitment was both miraculous and heroic.’’ And the poet Guy Owen, referring to one of Petrie’s earlier books, praised the poems’ sheer music: “The phrases that go on ringing and singing in the ear! My God!’’

The collection also tells the story of the Petries’ journey, from their courtship as young students in Iowa and travels in Spain, to Paul’s three decades of teaching at URI and happy family life in South Kingstown, where Sylvia still lives. “We were lucky,’’ she says. “We were so close.’’

He grew up in a blue-collar family in Detroit. His father worked in the press room of a newspaper and was an alcoholic with “eyes puffed and drinkshot,’’ which weighed heavily on the young boy. To make money, Paul delivered papers on his bike and worked in car factories, “Filing in through the low-arched gates/past the long vast looming buildings—/Spare Parts, Assembly, the gaunt/ Foundry’s mouth—and on/to Pressed Steel.’’

As a teenager, he dabbled in poetry writing, but he didn’t start to write in earnest until he arrived at Wayne State. Eventually, he landed at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, where he studied with Robert Lowell, among others, and earned his doctorate in creative writing.

They met at a table of graduate students in the cafeteria—Sylvia, a lively brown-eyed artist fresh out of Wooster College in Ohio, and Paul, a tall, lanky thinker with blue eyes and a mop of black hair. The poet asked the painter to go to a classical music concert. They fell in love quickly—and deeply. There were long walks by the river, Rogers and Hart in the music building, kisses in her room. Six months later, they were married:

Moon through the window look more lightly

upon my dear love’s breast.

Touch her with silver fingers, moon,

caressing and caressed.

The young couple and their cat, Goya, spent a year in Spain, then returned to America in time for the birth of their first child, Phil. They settled in Nebraska in a town called Peru, where Paul taught writing and celebrated the pleasures of fatherhood: “Like birds that tumble on the October air/ we roll upon the floor, unraveling joy/ like balls of colored twine. Against my face/ his face is soft and warm.’’

Paul joined URI in 1959, and although he enjoyed teaching, his shyness sometimes made it challenging: “Dry-mouthed, quick-beating heart/ I stand at the dark threshold/ of eyes/ and, smiling/ turn the knob.’’ His reward was sharing the “music, music, music’’ of Keats, Shelley, Wordsworth.

Two more children came along—Emily and Lisa—and days in the orange-doored Peace Dale house by the woods were filled with laughter, Bach and Brahms, and readings of Paul’s poems. On Sundays, he’d watch his beloved New England Patriots. Sylvia pursued her painting and printmaking, even collaborating with her husband on two hand-printed books.

“I was a slow poke,’’ she says. “He was the worker.’’ On writing days, he rose early, ate a bowl of cereal and drank a glass of milk, put on his down jacket for extra warmth and went back to bed. He wrote, usually in a spiral notebook, until noon. He always wrote lying down.

He was haunted by the march of time and death, the only certainty. Yet he didn’t let it wear down his enthusiasm, his sense of awe at being alive. Death, in Paul’s words, purified all living things: the “wintry theatricals” of branches, “half-shut buds of flowers,’’ the crow as “one black, heroic period in a world of flow.’’

The goldfinches outside his door were fed well. His family was a source of inspiration. In his poem “The Outsider’’ he watches from afar through “black-limbed trees” to the lighted windows of his house. Sylvia is setting the plates; the children are darting in and out at some unruly game; the dog is prancing behind.

I shall run to those yellow windows and hidden peer in—

I shall wrap them in silken handkerchiefs

like dolls—I shall sit all night in the moon,

weeping—weeping

for the past.

He retired from URI in 1991, but that didn’t slow him down. He was as productive as ever, adding to his canon of ten volumes of poetry and more than 400 poems in 100 literary journals, including The New Yorker and Poetry.

His illness was swift. A stabbing pain in his side brought him to the doctor. There were X-rays, and straight talk. Nothing could be done. The cancer had spread too far.

The night he died Sylvia read her favorites aloud, and then it was time to sleep. She lay down beside him. The room was dark. There was no gasping for air, no thrashing. His passing was peaceful.

“He was a wonderful man,” she says. “I think he felt almost a calling to praise life by ‘sounding the illicit heresies of joy.’ ’’ As expected, that philosophy surfaces in his work, “Poem for Joy.’’

“Page 649 in the book, stanza 5,’’ says Sylvia. He was a boy, singing as he rode his bike—hands free!—in the rain. Neighbors stared. The earth groaned. He sang louder, “both loud and clear,’’ until, through sheer force of will, he soared, “and the sea shrank back as he made the world.’’ •

Home

Home Browse

Browse Close

Close Events

Events Maps

Maps Email

Email Brightspace

Brightspace eCampus

eCampus