GSO professor bridges global research on PFAS contamination

November 12, 2024

Rainer Lohmann, professor at URI’s Graduate School of Oceanography and director of URI’s Steep Superfund Research Program, has returned from a Fulbright-sponsored research visit to Iceland, where he engaged in a collaborative exchange with scientists, government officials, and the public to deepen the study of PFAS—per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances—in Icelandic water systems.

The island nation, which is comparable in size to the state of Ohio, with a population of less than 400,000 people, has close ties with Europe, where regulations and environmental approaches differ from those in the United States. Lohmann was interested in studying PFAS contamination in Iceland, as it is far less industrialized and contaminated than the U.S., providing a unique opportunity to trace the sources of these chemicals.

During his visit, Lohmann delivered four guest lectures and participated in two public events organized by his Icelandic hosts, the University of Iceland faculty of Civil and Environmental Engineering. These included discussions with local experts, an open lecture titled Legacy and Emerging Pollutants from Land to the Arctic Ocean, and meetings with Iceland’s Environment Agency and its primary analytical lab responsible for seafood safety oversight.

“These discussions helped me gain a better understanding of the challenges of remediation and awareness of pollution in Iceland,” Lohmann said. “The country has limited experience and capacity actually dealing with contaminated sites, and PFAS treatments are very expensive.”

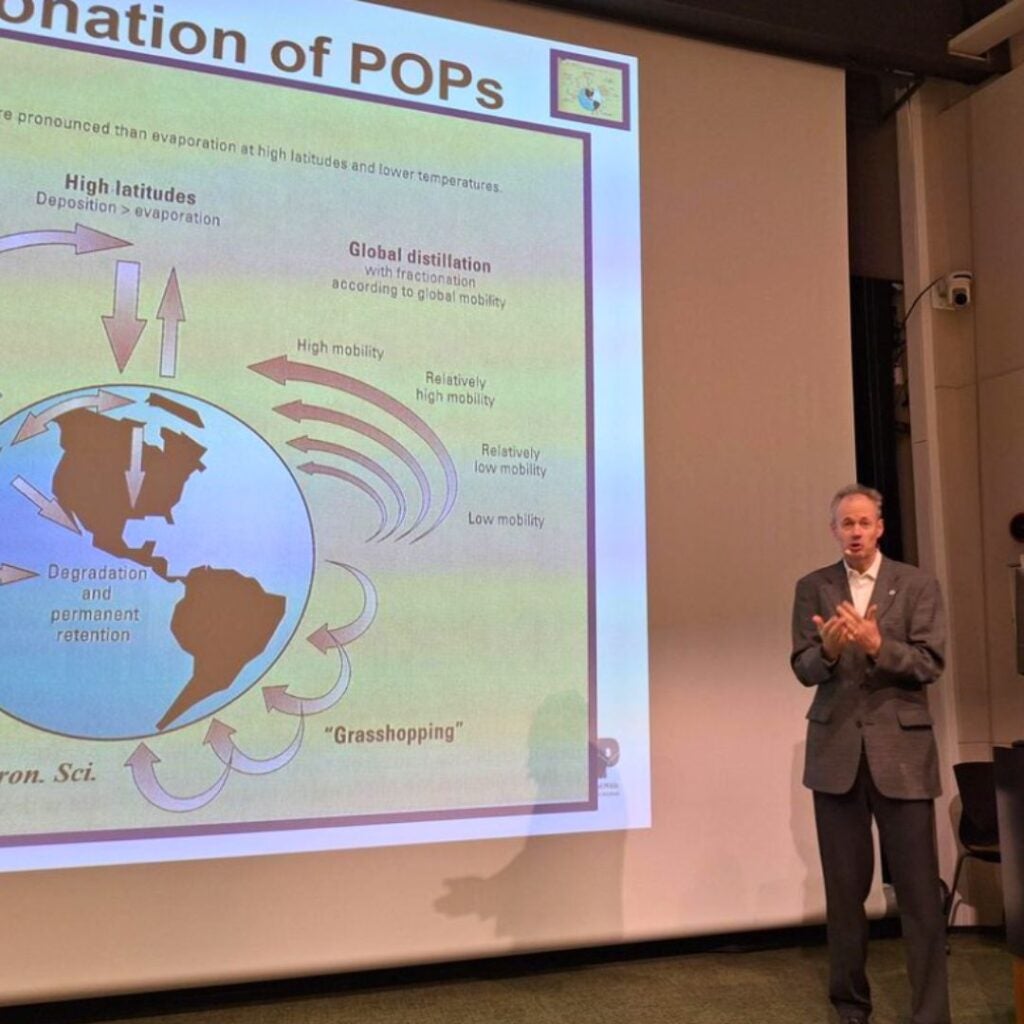

Before Lohmann’s visit, data on PFAS levels in Iceland was sparse, yet initial sampling efforts revealed relatively clean waters by international standards, though not entirely PFAS-free. Elevated levels, linked to prior use of aqueous film-forming foams, mirrored trends observed in the U.S. “Most PFAS detected in Iceland likely stem from locally used products, although some long-range transport from Europe and North America may impact marine fish populations around Iceland,” he explained. “The most cost-effective solution will be to limit the import and use of PFAS to protect their drinking water resources.”

In addition to presentations and meetings, Lohmann’s hosts arranged visits to sites critical to Iceland’s water management, including Reykjavik’s major drinking water wells, a wastewater treatment facility, and urban and industrial runoff areas.

Lohmann is one of over 400 U.S. citizens who share expertise with host institutions abroad through the Fulbright Specialist Program each year. His work with Icelandic scientists aims to raise awareness about these problematic chemicals and guide efforts to protect Iceland’s water resources from contamination. Beyond this collaboration, Lohmann’s experience lays the groundwork for future studies that will deepen understanding of PFAS in both Icelandic and U.S. environments.

This story was written by Mackensie duPont Crowley, digital communications coordinator with URI’s Graduate School of Oceanography.