Victoria Fulfer is visiting scientist at U.K.’s The National Oceanography Centre

June 2, 2023

While some of the most advanced and fastest ocean-going boats participate in The Ocean Race, a University of Rhode Island doctoral student is working in a lab in the United Kingdom analyzing samples collected by two of the boats on the presence of microplastics in waters around the world.

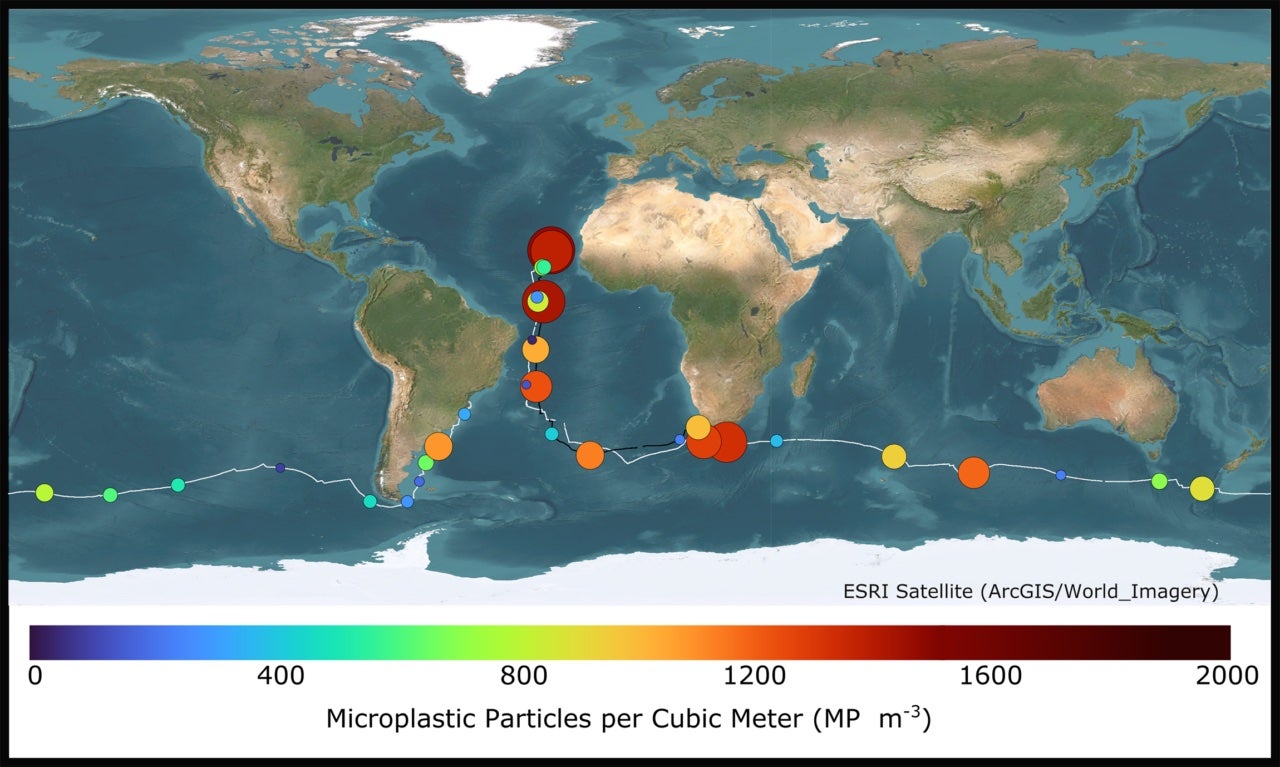

Victoria Fulfer, who is pursuing her Ph.D. in oceanography at URI’s Graduate School of Oceanography, is a visiting scientist at the United Kingdom’s National Oceanography Centre and is part of a team that has found high levels of microplastics in some of the most remote waters on the planet. Samples collected from two boats during two legs of the event have been analyzed by scientists at the center in Southampton, England. Other teams are collecting data on carbon dioxide and other vital ocean variables to help scientists that are studying the impact of climate change on the ocean. The two teams collecting plastic samples are GUYOT environnement-Team Europe and Team Holcim-PRB. Each boat is equipped with pumps and filters to collect water samples each day. See The Ocean Race’s release and video issued earlier this morning.

Leg 5, from Newport to Aarhus, Denmark, began May 21, with microplastics being collected throughout the about 37,000-mile race.

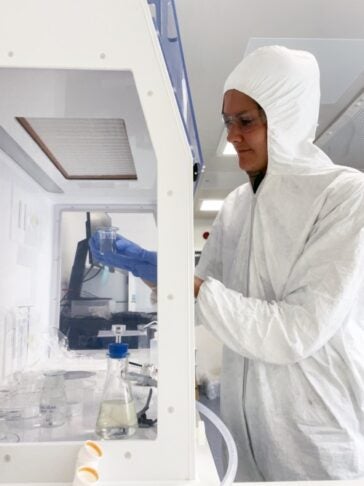

At the British lab, the microplastics are isolated from other materials in the filters and then scanned by a Fournier transform infrared microscope. Concentrations of microplastics in samples from the first three legs of the race ranged from 92 to 1,884 particles per meter cubed. Asked if 92 particles represent a minor issue, Fulfer said no.

Currently, Fulfer’s research is looking at samples that are 0.1 millimeter or 100 microns in size.

But she said that when particles are examined at a more minute level (0.03 millimeters or 30 microns), “you might have 2,000 to 3,000 particles per meter cubed.”

See The Ocean Race video featuring Fulfer and URI Professor of Oceanography J.P. Walsh, director of the Coastal Resources Center and Fulfer’s adviser.

“[When] we think of how many microscopic zooplankton, fish larvae and other organisms ingest these particles, it’s a pretty large problem,” she said. “There are so many studies showing that many fish and shellfish have microplastics in them, so even if we are seeing some concentrations that are not as high, they are still there. In some areas, particularly coastal areas, there are very, very high concentrations and that’s where most of our fishing occurs. So that is very concerning. But the areas that are very distant from land, where we have sampled only 92 to 100 particles per cubic meter, are also affected by the problem.”

She knows plenty about the coastal plastics problem. She was in Vietnam as a Fulbright Student Researcher from September 2022 to February 2023 researching plastic along the country’s beaches during the dry and monsoon seasons.

“It was astounding to see the amount of plastic washing up on the shoreline,” said Fulfer, who received a bachelor’s degree in cell and molecular biology and a master’s degree in oceanography from URI. “My work there showed how desperately we need better waste management practices.”

She was in Vietnam when her professor, J.P. Walsh, notified her of the opportunity at the center in the United Kingdom. Within a matter of weeks, she flew to her new assignment.

While discussing her research, she said, “I tell people the best way to reduce plastic pollution is to refuse to use plastic as much as possible.”

“Recycling is great, but it’s not enough,” Fulfer said. “We need to start thinking about alternatives to plastics. I study plastics and there are still times when you have to buy a plastic water bottle. But if people change their behavior in small ways, it can have really big impacts. Even though we can’t see them, microplastics are just like the terrible PFAS chemicals. They are accumulating in our food, water and in our bodies.

“One thing about The Ocean Race is we are getting samples from all over the world, and it presents a once-in-a lifetime data set for me as a scientist,” Fulfer said. “If we did this with a research vessel like the Endeavor, it would take a lot of time and a lot of money.”

While her journey as an oceanographer has led her to work on research vessels along coastlines and in Europe and Asia, her journey getting to and staying at UR has also been eventful. A Pennsylvania resident, she got hooked by URI when she first visited.

“I had never been to Rhode Island or URI when I applied, but I had always loved the idea of living in New England. To live by the beach, the ocean, excited me. I came here and I absolutely fell in love with it. I would not have become an oceanographer if I was not at URI,” Fulfer said.

Between her sophomore and junior years, she applied for a job at URI’s Narragansett Bay Campus and was hired to assist URI Professor of Oceanography Steven D’Hondt with his research. She worked with D’Hondt through the rest of her undergraduate years developing a database for his research on deep sub-seafloor life.

Two years after landing the job, she decided oceanography was what she wanted for her career, and D’Hondt became her professor and adviser as she pursued her master’s degree.

Now she can’t imagine leaving Rhode Island.

“But now that I have been living abroad the whole year in Vietnam and the United Kingdom, I have never loved Rhode Island more,” Fulfer said. “I realize how amazing living in Rhode Island is and being at URI is. I get to wake up in the morning and go surfing before work, and then when I go to my office, I can look out on the bay and see the Endeavor docked there.”

What does she hope to do when she completes her doctorate?

“The dream would be to work at a university, have my own lab, mentor students and continue to build a research enterprise around emerging contaminants and pollution in the marine environment,” she said. “If that doesn’t work out, the U.S. government, the Environmental Protection Agency, might be a good path.”

Oceanography professor Walsh, Fulfer’s adviser and director of the Coastal Resources Center where she works, said her goals make great sense.

“Victoria is tremendous and she is one of the most motivated students I have ever taught,” he said. “She always takes that extra step to figure out what to collect, how to collect it, how to analyze the data, graph the data, and then provide results in a visual, informative way.

Walsh also thinks Fulfer would be a great professor and researcher. “She is a natural, she will be a wonderful role model. She is a great, strong woman who can add to the field, but can also add character to any department or institution. The most fundamental thing about a faculty member or researcher is they are curious and want to keep learning. So that’s what I see in Victoria. She is always interested in learning more, looking at things from difficult angles.”