Temperature changes, lobster populations, and rockweed disappearance are all hot topics in Narragansett Bay right now and URI Graduate School of Oceanography (GSO) professor Candace A. Oviatt is right there in the thick of it, just as she has been for the last several decades.

She has every right to retire and relax on her favorite island, but no, the only change Candace has made to her GSO status in recent years is from “Full Faculty” to “Research Faculty” so she can concentrate on her research. In addition to her longevity, the amazing thing is that Candace has been rock steady all these years. She keeps working hard, she keeps calculating primary production, she keeps writing and publishing papers, and she keeps mentoring graduate students and summer interns.

What drives her? First, a scientist’s curiosity. Candace started out by simply trying to understand the components of this ecosystem that is Narragansett Bay. But over her professional lifetime she has seen major changes in the bay, so she also wants to document those changes and determine the best ways to manage Narragansett Bay and keep it productive, sustainable, and in balance. We are fortunate that Candace is willing and able to use her expertise for the greater good, to address the concerns of the people who work, live, and play in and along Narragansett Bay.

Her Early Narragansett Bay Studies

An undergraduate degree in Biology from Bates College whet Candace’s appetite for the sciences. She came to the University of Rhode Island in 1961 knowing little about the ocean (she had been raised in the inland part of Connecticut) but determined to learn about it and work towards her Ph.D. in Oceanography. There wasn’t much space at the Bay Campus so her first office was in Kingston, in what was the old Washington County Jail which had been converted into student offices. Eventually, she moved to the Bay Campus which looked alittle different from now, with only the Fish Building for offices and labs and the North Lab (the building now called Mosby) for tanks with running seawater. Candace was in a class of just two, the other student was Sheldon D. Pratt, who is still a GSO colleague. There were only 12 graduate students in the program and only two were women.

Candace’s dissertation work was on sea stars, or starfish as they called them then, which were a nuisance to shellfishemen because they preyed on clams and oysters. She was trying to find out how abundant they were in the bay and her traps collected scores, sometime hundreds. In trying to catch them, she found they were attracted to light. For more details go to Pell Library and look up her dissertation: C.A. Oviatt 1967, “Effects of artificial light on the movements of the common starfishAsterias forbesi (Desor). Or look at the peer reviewed article that was published from her dissertation: Light Influenced Movement of the Starfish Asteras Forbesi (Desor). Candace was the first woman to earn her Ph.D. from GSO, a distinction she received without fanfare.

Candace then took a post-doctoral position with the Harvard School of Public Health, but she did not travel far because her field work was in the waters off Block Island and Point Judith. The work, she says, “was very innovative”, using a manned two-person submersible to travel down to the seafloor. There she would place tin cans and other trackable materials to see what affect bottom currents might have on ocean disposal of incinerator waste. They were funded by the US Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA) for four seasonal surveys in one year.

Candace then returned to GSO as a Research Associate and worked for GSO Professor Nelson Marshall undertaking her first (of many) primary production measurements in the bay. Again, this was cutting edge work, using radioactive C-14 to look at production in benthic diatoms.

Partners in Ecosystem Studies

Because of her work in the bay, Nelson Marshall and John Knauss, the first Dean of GSO, knew that Candace would be the best person to introduce a new faculty hire from the University of North Carolina to all the intricacies of Narragansett Bay. But little did anyone know that this was the beginning of a very productive, lifelong, research partnership for Candace and Scott W. Nixon.

When Scott arrived at GSO in September, 1969, he and Candace were assigned Room 22 in the Fish Building to share as an office and lab space. They were each were given $11,000 in start-up funds for supplies and equipment for their work on Narragansett Bay. “Scott had a whole system perspective right from the beginning” said Candace. They decide to start small, studying Bissel Cove in North Kingstown. The resulting paper, Nixon, S. and C. Oviatt, “Ecology of a New England salt marsh,” Ecological Monographs, 43, 463-498, 1973, was one of the first published studies of whole ecosystems. Having gotten their feet wet and muddy in a smaller ecosystem, Candace and Scott were ready to tackle Narragansett Bay. Together they measured production and metabolism in salt marshes and eelgrass beds; examined fish community structure, populations, and their effect on the water column; looked at sediment resuspension; measured nutrient concentrations and fluxes, and even looked at the effect of man-made structures, such as marinas. Numerous papers were published. They were starting to understand the workings of the Bay.

Then, along with GSO professor Michael Pilson, they had what some thought was a crazy idea to build mesocosms on land that replicated water columns in Narragansett Bay. With funding from the USEPA and the expertise of dedicated marine technicians and research associates, in 1976 they had built the Marine Ecosystem Research Lab (MERL). The fourteen tall, cylindrical (1.8 meters in diameter and 5.5 meters in depth) mesocosms had a layer of Narragansett Bay sediments in the bottom and were filled with Narragansett Bay water. Here they could run long term experiments with different conditions (such as increasing levels of nutrients) in each mesocosm, another way to study the bay with a whole ecosystem perspective. One of the most well known experiments was a multi-year nutrient addition experiment, designed to examine eutrophication.

During the years of this research, Candace was promoted to research faculty and later to full faculty at GSO, one of the first women to attain that position.

Understanding the Changing Bay

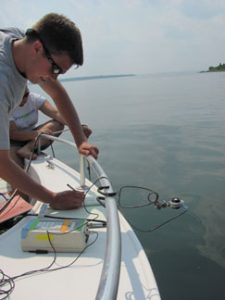

Today, Candace would be hard pressed to conduct her dissertation research since sea stars, after being almost wiped out by “sea star wasting disease”, are not easy to find in Narragansett Bay. This disease appears periodically, and the cause is still not known, but there was speculation that this latest occurrence was made worse by climate change. And mussels, which used to be ubiquitous on dock pilings, are also missing in the bay, for unknown reasons. So what can we look at in today’s Narragansett Bay? The MERL lab personnel are continuing to monitor the bay with buoy-based sondes that record temperature, salinity, oxygen, pH and chlorophyll, an important record to keep current.

“Climate change is coming down on us like a meteor” Candace says, so we need more temperature experiments. Candace is focusing her efforts and those of her students and interns on GSO’s shallow water mesocosms because the edges of the Bay, the intertidal and just subtidal areas, are more vulnerable to temperature changes.

Candace’s temperature experiments involve juvenile lobsters, which she thinks may be “the canary in the coal mine” for climate change. “But you also have to look at predation”, she cautions. Zooplankton graze on phytoplankton, as one example, and Candace is excited to note that we now have some recent zooplankton data. Predator populations are also affected by temperature changes and that in turn results in changes to their prey populations.

Candace is recognized worldwide as an expert on Narragansett Bay. In 2015 she received the Bostwick H. Ketchum Award from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution for “demonstrating an innovative approach to coastal research, providing leadership in the scientific community, and making a link between coastal research and societal issues”. That same year she received a “Lifetime Achievement Award” from Save the Bay, the non-profit environmental organization that works to protect and improve Narragansett Bay. In another measure of respect for Candace and her work, several years ago she was elected President of the Coastal and Estuarine Research Federation.

But not one to rest on her laurels, Candace can still be found most days either at the mesocosms or in her office at MERL where she is often writing and doing calculations. Her most recent published research paper, with a number of co-authors, came out last year: “Managed nutrient reduction impacts on nutrient concentrations, water clarity, primary production, and hypoxia in a north temperate estuary.” According to her latest calculation, Narragansett Bay-wide primary production has been reduced (to 200 gC m-2 y-1 compared to 320 gC m-2 y-1) since the current nitrogen reduction at wastewater treatment facilities. This means we can manage our human inputs to the bay and see changes in other parts of the ecosystem. Which is why it is so important to look at the ecosystem as a whole, a perspective Candace has had for a long time.

September 25, 2018 Volume 1, Number 6.

This blog post was written by Veronica M. Berounsky, GSO Science Correspondent and Coastal Ecologist. She first arrived at GSO in March of 1979 as a research lab tech. In 1990 she obtained her Ph.D., working on nitrification in Narragansett Bay with the late Scott W. Nixon. She continues to be fascinated by the ecology of coastal ecosystems every day. With this blog she hopes to increase your understanding of the activities and people of GSO and the Narragansett Bay Campus. Please email any comments to her at vmberounsky@uri.edu.

This blog post was written by Veronica M. Berounsky, GSO Science Correspondent and Coastal Ecologist. She first arrived at GSO in March of 1979 as a research lab tech. In 1990 she obtained her Ph.D., working on nitrification in Narragansett Bay with the late Scott W. Nixon. She continues to be fascinated by the ecology of coastal ecosystems every day. With this blog she hopes to increase your understanding of the activities and people of GSO and the Narragansett Bay Campus. Please email any comments to her at vmberounsky@uri.edu.

Click here to see all previous posts.

Subscribe to the Bay Campus (B)log here